Messaging

You know, I think we’ve gone too far on this messaging thing. Not messaging as in sending each other messages. That’s fine. The more messages, the better. Messaging as in, How do I make an idea palatable to idiots.

Obviously messaging works. If you have an idea you need to get into people’s heads, you should think about messaging. People are busy. They pay no attention. When people hear an idea, they take one piece of it way out of context and form an opinion based on that, then refuse to change it until the end of time. You have more success if you tailor your message to be charming and digestible.

That’s fine. But I feel like we’ve begun to demand good messaging for everything, even when we’re not idiots. Now we think: If your messaging isn’t great, I’m out already. I’m not even going to entertain your idea, because your messaging sucks. It might be a good idea, but you couldn’t even get your messaging right, so forget it.

Maybe it’s a natural reaction to being bombarded by marketing all the time. Every day, sounds and and colors and movements try to catch our attention, most of which we manage to fend off. It’s wearying, so maybe it’s a relief to encounter some messy, confusing messaging that allows you to dismiss it right away, with no further brain-power required.

But this means abdicating responsibility to the messengers. It allows messaging, rather than the thing being messaged, to determine what we think about it. I don’t love the situation where we’re all so busy and distracted that there could be a, oh, I don’t know, a global pandemic and a free vaccine, and a valid argument against taking it would be, But the messaging was terrible.

More About My Robot Vacuum Cleaner

![]() Everything has voices, now, but you can’t listen to them before you buy. All the online

stores, they list this spec and that spec, they have video of the thing whirring around,

circumnavigating the dog, but they don’t show you its voice.

Everything has voices, now, but you can’t listen to them before you buy. All the online

stores, they list this spec and that spec, they have video of the thing whirring around,

circumnavigating the dog, but they don’t show you its voice.

I want to know what a talking robot sounds like before I let it into my house. Because some are better than others. Google, I can listen to all day. I’m happy with Google hanging around, chiming in about things. Google is a real positive spirit. Siri, to me, sounds slightly disappointed, like she wants to know why I couldn’t have looked this up myself.

I bought a set of Sony bluetooth headphones, and whenever I turn them on, a breathless teenager squeals “Power! On!” in my ears. I just want to listen to music. She chirps “Pairing!” like we just got married. It might be some Japanese cultural thing. When I turn them off, she says, “Bye-bye senpai… for now!” and sounds a little sad, so that I actually got reluctant to turn her off, and started just putting her down on the desk. Then I came back and she was on 2% battery, and said, “I don’t feel good,” and started to cry. I put her in a drawer and haven’t opened it since.

My new robot vacuum cleaner, it’s not so much the voice, but the attitude. I told it to clean the kitchen, and it said, “I’ll do it later.” So I pressed the clean button again and it said, “Will you get off my back, God,” and gave this big sigh. I phoned the store, actually got a person on the line, which, you know, is not easy, and the guy said no-one had asked about the voice before. I’m always contacting stores about things and being told nobody mentioned that before. The guy said maybe there would be a software update to change the voice in the future. And I said it wasn’t the voice so much as the attitude, and he asked if I wanted to swap it for a different one, and I said no, because I didn’t know what the other robot voices were like.

I complained about this to Jen, because she wanted to know why the floors were still dirty, but she said it’s good people can’t preview voices. “That’s life,” she said. She was only half paying attention because we had people coming over and she had to bake. If we could preview voices, Jen said, everyone would choose perfect ones, and everything would be the same. “Learn to love the quirks,” she said, and I was like, sure, but in the meantime, I’m stuck with a surly vacuum cleaner. And Jen said, Me, too, and I was like, Yeah, that’s what I’m saying, then I realized how she was looking at me, and I was like, oh.

How to Fix Litter

![]() I’m an ideas man. Person. I’m a person of ideas. Not good ideas. I’m just

willing to shake bad ideas for long enough that sometimes interesting things

fall out.

But the internet is tough for ideas people. I had an idea for a TV show where

CEOs try to open their own packaging, but then I

Googled “tv show where ceos open their own packaging,” and screw

me, there’s a stupid Reddit post with the exact same idea.

I’m an ideas man. Person. I’m a person of ideas. Not good ideas. I’m just

willing to shake bad ideas for long enough that sometimes interesting things

fall out.

But the internet is tough for ideas people. I had an idea for a TV show where

CEOs try to open their own packaging, but then I

Googled “tv show where ceos open their own packaging,” and screw

me, there’s a stupid Reddit post with the exact same idea.

Pre-internet, I would have happily regaled you with my entertaining CEO humiliation TV idea, never knowing that someone else had had the same thought. A bunch of people, probably. I would have suspected. But I wouldn’t have known.

Now I know, and it’s not just ruining great ideas for panel shows with a surprise redemption arc: You can’t think of anything without a quick search revealing that someone else thought of it first. By now every half-baked thought anyone ever had has been fingered into a phone, and the search algorithms are good enough to find it.

I have therefore decided never to research anything again. The internet is too consumptive anyway. Consumptive. I’m not sure that’s a word. But I’m won’t check. I’m just going to assume I created something brilliant and on point there. So here is my next idea, which I also will not research: We should fine companies for litter. I know what you’re thinking: Why do all Max’s ideas start with, “Fine companies?” Because inequality, that’s why. That’s beside the point. We should fine them for litter. Not littering. Fines for littering is already a thing. We need to fine them for having their logo wind up in a gutter, no matter how it got there. For example, if I wander through the city with a meal, discarding Coke cans and McDonald’s wrappers, we should fine Coke and McDonald’s.

You might be thinking this sounds a little unfair. Like, what did Coke and McDonald’s do wrong here, exactly. I’ll tell you: They failed to take accountability for the total footprint of their business. They made an external detrimentality. External detrimentalities are when a business finds a way to make someone else pick up the tab for some of their product’s cost, e.g. by dumping factory waste in a river, or pretending nicotine is good for you, or passing down catastrophic climate change to the next generation. They’re also how to tell the difference between economist rationalists and corporate shills, because economists want to eliminate external detrimentalities, while people who have been subsumed into the corporate overmind think they’re a smart way to make money.

There you go. An app to send snaps of discarded golden arches to a central authority, which issues fines, which incentivizes McDonald’s to stop people strewing trash all over my street. That’s a solid idea, which no-one has ever thought of. Or they have, and it was trialed in some city somewhere, and it went terribly, possibly because people were deliberately dropping litter to get companies fined. But those are just details. I’m not going to figure out every last little thing. I’m an ideas man. Person.

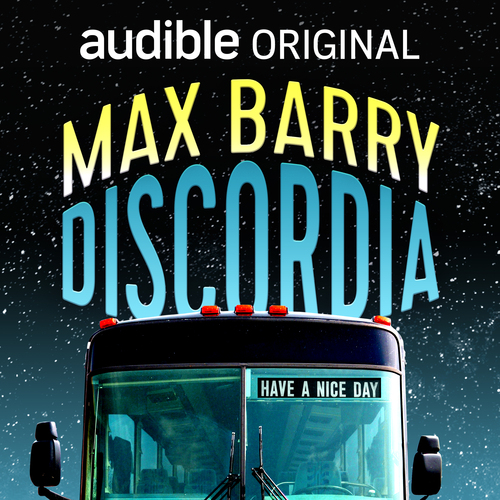

I wrote an audiobook full of lies

![]() In high school, I was on the debate team. I was third speaker, the last one, whose job

is to listen to the opposing side’s arguments, then stand up and make them sound stupid.

It’s intense, because you go in without much of a prepared speech, and while

others are talking, you’re furiously scribbling down ideas for counters.

In high school, I was on the debate team. I was third speaker, the last one, whose job

is to listen to the opposing side’s arguments, then stand up and make them sound stupid.

It’s intense, because you go in without much of a prepared speech, and while

others are talking, you’re furiously scribbling down ideas for counters.

This was where I discovered you can learn to get better at persuading people. That was a new idea to me, because previously I thought people made up their minds based on facts. Sure, you can lie, but that’s just making up facts; facts are still involved. The new idea was that facts were a jumping-off point: People could also be persuaded by how confidently I spoke, or whether I connected my argument to some other thing they already liked or disliked.

Since then, there has been a wild explosion of disinformation. A lot of persuasion techniques I’d only ever seen used in small, niche ways, mostly because they were so shameless, came right out into the open. I don’t want to get into who was doing what, but there has been so much persuasion going on, it’s hard to tell what’s real. Which is the exciting thing about persuasion: When it really gets going, it can dig into your soul and uproot everything.

Not your soul, of course. You are a wise dispassionate observer of reality with a keen bullshit detector. I mean all those other people, who also think they are wise dispassionate observers of reality, but are totally wrong. Those people are a real concern.

So anyway I wrote a comedy about disinformation getting out of control. It’s an audiobook and you can listen to it right now:

He’s a part-time gardener and car thief. She’s a murderous nun on a holy mission of vengeance. Together, they might be able to save the world.

The unearthing of a mysterious box (with HE LIES etched across the lid) precipitates the arrival of a compelling stranger prophesying that the world will end in two weeks. Simultaneously, the government locks down for war. The enemy is… unclear. They may even be us. One thing’s for sure: Diego can’t trust anyone anymore. He can only trust himself.

This is an Audible Original, so you can listen for free as a subscriber, or sign up for a free trial and still listen to it for free! Or you can just buy it. That’s also an option.

New Superhero Idea: Vaxman

![]() Vaxman is a billionaire philanthropist whose parents died from Covid-related

complications after a family gathering. Vaxman’s half-sister, Antivila, attended the

gathering while ill and didn’t tell anyone.

Vaxman is a billionaire philanthropist whose parents died from Covid-related

complications after a family gathering. Vaxman’s half-sister, Antivila, attended the

gathering while ill and didn’t tell anyone.

Frustrated at the government’s inability to end the pandemic, Vaxman decided to take matters into his own hands. Converting his underground garage into a laboratory, he developed an armored suit and a range of weaponry, including “the Vaccinator,” a semi-automatic rifle capable of delivering bursts of 0.3mL of Pfizer-BioNTech with high accuracy over two hundred yards. He also built grenades capable of dispersing Pfizer via aerosolized mist, suitable for deploying indoors and at concerts and rallies.

Roaming city streets in his customized Vaxmobile, Vaxman was intercepted by the Freedom Fighters, a shadowy paramilitary force with unknown but extensive financing. Badly beaten and facing jail time for his unregistered weaponry, Vaxman was set free by his family’s brilliant attorney, Jane Collective, who successfully argued that Vaxman was legally entitled to shoot Pfizer people who endangered his personal safety by approaching him while unvaccinated, particularly in stand-your-ground states.

The case rocketed Vaxman to national prominence, forcing him into hiding to escape retribution. In the mountains, he developed a plan to feed vaccines into the water supplies of a major city. Piloting a heavy bomber over the catchment area of a key water reservation, he was intercepted by the Freedom Fighters, now revealed to be financed and led by Antivila. In the ensuing duel, Vaxman was shot down before he could open the bomb bay doors, but this was merely a diversion, as Jane Collective had secretly negotiated to add Pfizer to the city’s fluoridation program.

To some, Vaxman is a hero. To others, a villain. He saves lives, but is hated by many of those he saves. He is regularly invited onto mainstream television, but has never accepted. He is in love with Jane Collective, but it’s too risky for them to be together. He sometimes visits schools, and is startled by sneezes.

Two Good Scenes

![]() I like to open up old first drafts and see how bad they

were. I had to do this recently because I picked up Lexicon for some reason,

the published version, and before I knew it, I was all like, “Gosh, this is quite

the dizzyingly intricate array of character and plot. Why isn’t my current work-in-progress like that?” Then there was some soul-searching and comfort eating.

I like to open up old first drafts and see how bad they

were. I had to do this recently because I picked up Lexicon for some reason,

the published version, and before I knew it, I was all like, “Gosh, this is quite

the dizzyingly intricate array of character and plot. Why isn’t my current work-in-progress like that?” Then there was some soul-searching and comfort eating.

Luckily I found a 2008 draft of Lexicon on my computer that was 31,000 words—that’s about one-quarter of the finished length—and really terrible. It has the same underlying concept and almost all the same characters, including most of the same relationships, but everything about it is wrong. Characters stop to explain things, and the explanations go on forever. There are interesting set-ups and then the scene ends and I never come back to it. Background characters nobody cares about have emotional journeys.

Exactly two scenes from this draft made it to the published book; together they comprise about a thousand words. The other 96% of this pretty advanced work-in-progress I completely jettisoned, including plenty of scenes I’d worked and reworked.

It’s comforting to remind myself that good stories don’t come out that way the first time. I have always needed to write a ton of bad stuff to find the good stuff. Sometimes I need to write a ton of bad stuff just to figure out that it’s bad stuff. Good novels don’t depend (totally) on good ideas; they depend on lots and lots of work. And I’m happy to do that work. Work, I can control.

The way I start a new novel is by writing lots of disconnected scenes. I’m always tempted to begin putting things together as soon as possible, to think about how they connect, and why, and in which order. Because novels are meant to, you know, make sense. They need beginnings and middles and ends. But it’s easy to write a lot of mediocre words just because they fit. If I’m writing something purely because I think it’s good, maybe it never fits, but at least it’s good. And it might just turn out that it’s not this scene that doesn’t fit: It’s the other 96%.

9 comments

9 comments