Being Wrong is Okay

![]() I got some hot mail following my last blog. Some really hot mail. To summarize:

I got some hot mail following my last blog. Some really hot mail. To summarize:

You (Max) said it’s wrong to do nothing about feminist issues

I (a good guy) do nothing about feminist issues

You think I’m a bad person so SCREW YOU IN THE FACE

This feels like a real misunderstanding. Sure, I think you’re wrong, but that doesn’t make you a bad person. We all believe wrong things. I have a bunch of wrong beliefs right now, I bet. Not this one. This one, I feel confident about. But I’m sure I have others, which I’m yet to identify. Because we’re not born with the answers; we have to figure this stuff out.

Curiously, almost all the hot mail focused on how I should stop apologizing and feeling guilty for being male. I say “curious” because at no point in my blog did I apologize or mention guilt. People just assumed that’s what happens if you’re wrong: You feel shameful and want to apologize.

This is a pretty dramatic view of wrongness. We’re not wrong every few years. We’re constantly wrong. We generalize; we don’t pay attention; we are a wacky collection of hilarious biases. Being wrong doesn’t make you a bad person: It makes you a person. It’s what we do on the regular so we’re not stuck with the same ideas we had when we were fourteen.

I think a lot of dudes, including me, haven’t done anything particularly terrible, but haven’t been particularly helpful, either. That’s not a crime. But it’s not great, either. When we see entrenched unfairness—even the quiet, casual kind, which is surprisingly hard to spot, when it doesn’t directly affect you—the right thing to do is call it out. And to try harder to see it.

That’s it! Because, and I may be off-base here, I don’t think a whole lot of women care about men apologizing or demonstrating guilt. I think mostly they’d just like us to be more helpful. Nobody’s end goal is to make dudes feel bad. This isn’t even about dudes: It’s about making the future fairer. If all that means to you is shame and guilt, well, okay, you can feel that way, but it’s probably not helping anyone, and no-one asked you do it.

Nothing Against Women

![]() Boy we’ve become smart about feminism. Way back when I was young,

if you were a dude who wasn’t a feminist, you told girls to make

you a sandwich and sexually denigrated them in the workplace.

But actively vocalized misogyny has become pretty uncool since then,

so we had to come up with something new. And we did! It’s: Nothing.

Boy we’ve become smart about feminism. Way back when I was young,

if you were a dude who wasn’t a feminist, you told girls to make

you a sandwich and sexually denigrated them in the workplace.

But actively vocalized misogyny has become pretty uncool since then,

so we had to come up with something new. And we did! It’s: Nothing.

Nothing is great. Nothing works almost as well as active misogyny, with the added benefit of not requiring you to do anything. Also people can’t complain about you doing nothing, because you’ve literally done nothing.

The way nothing works is you just go about your business and ignore anything not directly relevant to your own life. This is the default for most people, so it’s pretty simple. But you can really make it work when you’re operating in an environment set up in your favor. In that situation, doing nothing grants you benefits without requiring you to come out and explicitly endorse the system you’re benefiting from, which would be, you know, awkward and uncool.

There are lots of ways to profitably do nothing as a dude. One of my favorites is not to profile violent people for being male. If there’s a riot, a shooting, any kind of major crime, we’ll dive right into a conversation about whether it’s fair to observe that the perpetrators are a particular ethnicity or English soccer fans or whatever. We will be all over that discussion. We’ll hit it from every angle: transparently racist, excessively apologist, whatever. But we won’t say a word about how ninety-plus percent of the perpetrators are dudes.

I really want a riot with 95% women looting stuff and punching people, just to see how how fast the media fills up with hot takes. Not a women’s issues protest: a riot in which all the assaults and property damage just happen to be committed by women for no obvious reason. I don’t know what we’d conclude about that, but I guarantee we’d discuss it. We would discuss that to death.

Another great one this year is vaccines. I’m not sure if you heard, but a few of them (like AstraZeneca) have an almost-but-not-quite-zero chance of causing blood clots. This caused angst about whether they were truly safe, particularly in places where there wasn’t much COVID. But we forgot about contraception, and out came media pieces like: “Oh, we’re talking about unlikely but dangerous side-effects of medication? Can we discuss the pill?” Because the contraceptive pill causes blood clots (albeit far less dangerous ones) at a hundred times the rate of AstraZeneca, and has a list of other side-effects that are also very unlikely but serious.

Obviously we’re beyond the time when we could tell women to stop worrying their little heads about the pill while we deal with this unacceptably dangerous AstraZeneca situation, so instead we did nothing. We just didn’t say anything. We didn’t click the pill articles; we didn’t retweet; we didn’t post. They weren’t that relevant to us. Within a week, they all died from lack of attention, and six months later we’re still talking about AstraZeneca.

We closed the golf courses in my city for a while during lockdown. Holy hell, was that a discussion point. We filled the airwaves with talk about whether it was fair or a terrible injustice. I’m pretty sure other sports and recreational activities were in similar situations, but I barely heard about them.

I remember a time when I thought I shouldn’t have to cross a road to avoid alarming a woman walking alone at night. Because if we want equality, shouldn’t I equally be able to walk wherever I want? I marvel at that perspective now, because it requires almost total blindness to the inequities women face. I had a spotlight that only illuminated the part of each issue that directly affected me. An environment causing women to fear for their safety: nothing to do with me. My potential inconvenience: civil rights issue. I outgrew that, mostly, I hope, but still, it has been a journey of discovery, with each discovery looking very obvious in retrospect, so that I wonder how I failed to notice it earlier. I’m sure that isn’t over, and, of course, it’s part of a wider road that covers more than just feminism. But in the meantime, I aim to do less nothing.

You know—I was going to finish this piece there, but it struck me that I genuinely expect you to be satisfied that I’ll try to do better than nothing. That’s amazing, isn’t it? I can benefit from gender bias my whole life, and keep all those benefits, plus any I may accrue in the future, but so long as I try to avoid being a silent co-conspirator in any future oppression, that’s pretty good. That is one low bar.

99%

![]() If you do one thing each day that has a 99% survival rate, you’ll likely be

dead in under ten weeks. If boarding a plane had a 99% survival rate,

a typical flight would end by carting off at least one passenger in a body bag,

perhaps two or three. Ninety-nine sounds close enough to 100, but anything

with a 99% survival rate is incomprehensibly dangerous.

If you do one thing each day that has a 99% survival rate, you’ll likely be

dead in under ten weeks. If boarding a plane had a 99% survival rate,

a typical flight would end by carting off at least one passenger in a body bag,

perhaps two or three. Ninety-nine sounds close enough to 100, but anything

with a 99% survival rate is incomprehensibly dangerous.

Go sky-diving, and you’re over two thousand times safer than if you were doing something with a 99% survival rate. Driving, the most dangerous everyday activity, requires you to clock up almost a million miles of travel before you’re only 99% likely to survive. Even base jumping, perhaps the single most dangerous thing you can do without actively wanting to die, is twenty-five times safer than anything that carries a 99% survival rate.

Ninety-nine bananas is essentially one hundred bananas. Ninety-nine days is practically a hundred days. But 99% is often not even remotely close to 100%. It feels like similar numbers should lead to similar outcomes, but the difference in life expectancy between 99% and 100% survivable daily routines isn’t one percent: It’s ten weeks versus immortality.

It’s simple enough to calculate the probability of more than one thing happening:

You just multiply the individual probabilities together. The likelihood of surviving

for three days, for example, while doing one thing per day with a 99% survival rate,

is 0.99 x 0.99 x 0.99 = 0.9703, or 97.03%.

But we find this deeply counter-intuitive. We prefer to think in categories, where

everything can be labeled: good or bad, safe or dangerous, likely or

unlikely. If we have an appointment and need to catch both a train and a bus, each of which

have a 70% chance of running on time, we tend to consider both events as likely, and

therefore conclude that we’ll make it. The actual likelihood

that both services run on time is 0.70 x 0.70 = 0.49, or only 49%: We’ll

probably be late.

We also prioritize feelings over numbers. Here’s a game: Pick a number between 1 and 100, and I’ll try to guess it. If I’m wrong, I’ll give you a million dollars. If I’m right, I’ll shoot you dead. Would you like to play?*

Most people won’t play this game, because the thought of being shot dead is too scary. It’s shocking and visceral, so when you weigh up the decision, both potential outcomes balloon in your mind until they feel roughly equal, as if the odds were 50/50, rather than one being 99 times more likely than the other.

But put the same game in a mundane context — if instead of being shot, you get COVID, and instead of a million dollars, you just go to work as usual — and we tend to return to categorical thinking, where the dangerous-but-unlikely outcome is filed away as too improbable to be worth thinking about. As if close to 100% is close enough.

Between 99% and 100% lies infinity. It spans the distance between something that happens half a dozen times a year and something that hasn’t happened once in the history of the universe. With each step we take beyond 99%, we cover less distance than before: 1-in-200 gets us to 99.50%, then 1-in-300 to 99.67%, then 1-in-400 only to 99.75%. We’ve quadrupled our steps, but only covered three-quarters of the remaining distance. We can keep forging ahead forever, to 1-in-a-thousand and 1-in-a-million and beyond, and still there will be an endless ocean between us and 100%.

You have to watch out for 99%. You have to respect the territory it conceals.

Resist lunch.

![]() Sometimes I exaggerate a little because I want your attention and also to be funny.

I just want to say: This is not one of those times.

Sometimes I exaggerate a little because I want your attention and also to be funny.

I just want to say: This is not one of those times.

Lunch is wrong. Lunch is one of the worst things there is. If I’m ranking bad things, I would go: cancer, lunch, heroin. Lunch is worse than heroin because the number of people who can’t go twenty-four hours without heroin is relatively small.

I know how this sounds. I’m well aware of the futility of going up against Big Lunch. You people have spent your lives addicted to lunch. You need lunch, at this point. You can’t imagine life without it, nor do you want to. Let me observe that these are things junkies say.

Here are the hidden dangers of lunch:

It costs money

It makes you tired while your body digests it

Maybe that seems fine to you. Money and tiredness: a small price to pay for lunch. That’s only your financial position and your ability to function. Honestly. Listen to yourselves.

I first tried no lunch when my writing was going well and I didn’t want to stop. I felt hungry and light-headed but also noticed that I got through the day without feeling like a useless sack of potatoes by 4pm. So I tried it more often. Sometimes I felt light-headed, and hallucinated a little, and became underweight, but none of these are problems for a writer. They help, if anything.

I know what you’re thinking: “Max, it kind of sounds like you have an eating disorder.” Well, let me tell you something. You might be right. I have actually started to doubt myself while writing this piece. Maybe it’s not actually the world that’s weird; maybe it’s me.

No. I think it’s you. Because I’m not slavish about no lunch. I actually eat lunch pretty often. Just not, you know, every single day. So I think that puts me morally in the right, because I can stop eating no lunch whenever I want. I’m not addicted to no lunch. I just use it strategically to get stuff done.

I won’t eat bread, though. Bread is the worst. Eating bread for me is like injecting fatigue into my brain stem. I can run six miles and feel full of energy, but after half a sandwich, I need a nap. I’m not sure if it’s the gluten or just that bread is packed full of evil. Either way, I’m not a fan.

I also listen to dangerously loud music because it helps me write, and I’d rather write well than hear everything at eighty. I’m not sure why I mentioned that. That’s not related to anything.

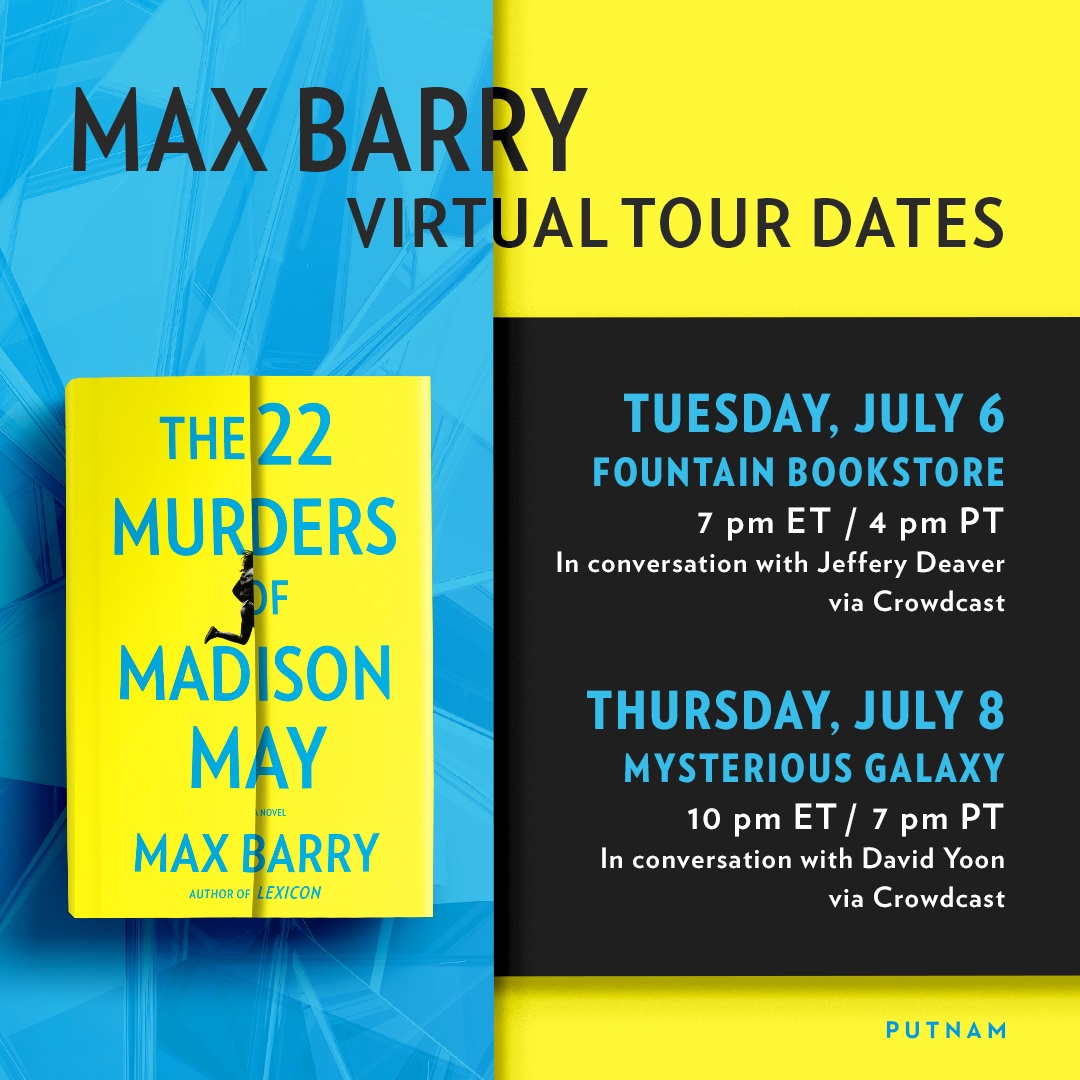

An Evening With Max: Two Online Bookstore Events

![]() A long time ago, before you were born, you could go to bookstores

and hear authors speak. They would shuffle out to a podium and maybe read from their

new book and answer questions about their process. It was a simpler time.

A long time ago, before you were born, you could go to bookstores

and hear authors speak. They would shuffle out to a podium and maybe read from their

new book and answer questions about their process. It was a simpler time.

But now! It’s online! All the time! Everything is online! Including me!

Check out who I’m in conversation with. That’s right. First, Jeffery Deaver, then David Yoon. Those are some heavy hitters. I am getting totally respectable.

Here are some handy links to register & see the local time wherever you happen to be in the world. Because for me, it’s the morning the next day. I will literally be dialing in from the future.

Register here for Tuesday July 6 at 7pm ET / 4pm PT: Launch party in conversation with Jeffery Deaver, hosted by Fountain Bookstore.

Register here for Thursday July 8 at 10pm ET / 7pm PT: In conversation with David Yoon, hosted by Mysterious Galaxy.

Tickets are going fast, so get in quick! I’m joking. There is no limit on tickets. It’s an online event.

But you should register so they can send you info on how to join. Then you’ll see me! Talking! Answering your questions! Like a real person! Enjoy it while it lasts, because after all this promotion hoopla I seriously need to get back to writing.

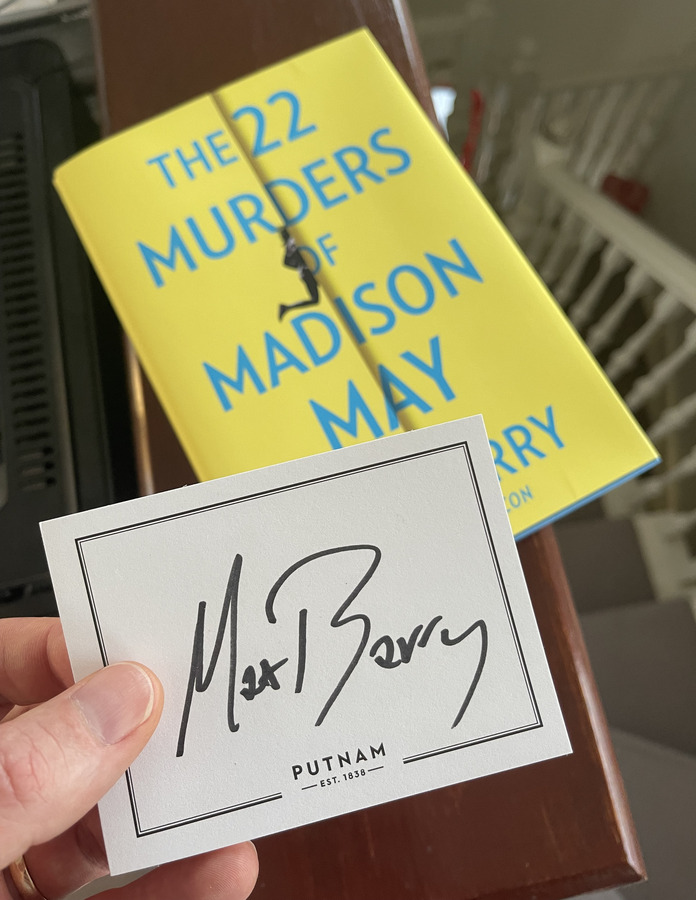

This is also the only way to get signed copies of The 22 Murders of Madison May, if you’re interested in that. I signed bookplates and mailed them to these two stores and they will stick one in any book you order. Well not any book. Any book written by me. They look like this:

I also gently kissed each card. Not really. That wouldn’t be COVID-safe. But I wanted to.

The new book: The TV show

![]()

My new book, The 22 Murders of Madison May, is out next week in most of the world, and today in Australia and New Zealand. Now there is a TV show in development, too! This has been brewing for a while and today made it into the pages of Variety. So it’s official and I’m allowed to talk about it.

My new book, The 22 Murders of Madison May, is out next week in most of the world, and today in Australia and New Zealand. Now there is a TV show in development, too! This has been brewing for a while and today made it into the pages of Variety. So it’s official and I’m allowed to talk about it.

This is exciting firstly because it’s, you know, a TV deal, but also because it’s at MGM’s Orion Television, with show-runners Meredith Lavender and Marcie Ulin, who served the same role for The Flight Attendant. That was one of the more interesting new shows of last year, and lives in a smart / funny / endearing thriller space I like a lot.

What will happen next is Meredith and Marcie will go write a pilot script. Then, I can tell you, because this isn’t my first rodeo, this script will bounce between a bunch of people and be rewritten until either it’s good enough to get made or the studio is acquired or shut down. It is a race between those outcomes.

I’ve been lucky enough to have many books acquired for TV or film development (ten years ago, always for film; today, always for streaming TV), and even though it’s a crapshoot as to whether they work out—there are more rights acquisitions than TV shows—the process is fascinating and thrilling. When someone adapts my work, I feel like my story gets a new baby sibling: an addition, not a replacement, and I can admire the similarities and the differences. Also, if it actually winds up being produced, I get to see sets and actors dressed like people I imagined, which is a genuinely magical experience, like finding a door at the back of my closet to a place I always suspected was real.

So I love that I get to do this again.

9 comments

9 comments