Corporate Persons are Jerks! http://www.bigfatwhale.com/archives/bfw_446.htm

Corporate Persons are Jerks! http://www.bigfatwhale.com/archives/bfw_446.htm

The Lawnmower People

![]() I was all set to do a blog about how using Windows is like growing evil tomatoes,

then American corporations became real people. They’ve been people for a while,

of course: they have the right to own things and sue you and claim they’ve been

defamed. Your chair can’t do that. A corporation can, because it’s a person.

I was all set to do a blog about how using Windows is like growing evil tomatoes,

then American corporations became real people. They’ve been people for a while,

of course: they have the right to own things and sue you and claim they’ve been

defamed. Your chair can’t do that. A corporation can, because it’s a person.

But they weren’t enough of a person, apparently, so now they have First Amendment rights. In particular, they have the right to spend as much money as they like on political advertising: airing ads in favor of anti-regulation candidates over pro-regulation ones, for example.

I find it helpful to think of corporations as lawnmowers. Lawnmowers are good at cutting grass. It’s all they want to do. They’re not very concerned about what gets in the way of cutting grass. If, for example, we discover that one of the lawnmowers sometimes kills people, the lawnmower would rather pretend there isn’t a problem than stop mowing lawns. It seems callous to us. But you have to remember, it’s not a person. It’s a lawnmower.

Corporations pursue profit; the fewer people watching, the more ruthlessly they do it. It’s not coincidence that Apple is a relatively nice corporation and Halliburton is not. It’s not that Apple was raised right while Halliburton had a distant father. It’s that Apple’s profits depend more heavily on consumer opinion. It can’t make money unless it’s likable, so it is.

I think lawnmowers are useful. I don’t want to get rid of them. But I very much want to keep them on the lawns.

The Supreme Court has let them into homes: now the lawnmowers will speak to us through TV, radio, internet, print, and tell us who to vote for. That might not seem like a problem. After all, you are a smart person. You’re probably not persuaded by advertising. The thing is, everyone thinks that, and advertising is an $600 billion industry. Someone, somewhere is getting $600 billion worth of persuasion.

It’s pretty obvious that lawnmowers will back pro-lawnmower candidates. They are functionally and legally prevented from doing anything else. In fact, now that the opportunity exists, lawnmowers are compelled to exploit it.

Honestly, I had started to think that the world of Jennifer Government was getting far-fetched. It seemed like corporations were not overpowering the government at all; instead, the two were slowly merging into a govern-corp megabeast. But this changes things. Until now, corporate lobbyists have essentially stood in opposition to voters: politicians wanted lobbyist money, but resisted giving in too much for fear of being punished at the ballot box. Now corporations can work it both ways. They can buy off the politicians and sell the voters on why that’s A-OK. They won’t have to come up with the media messages themselves. That’s a job for the ad agency. All they’ll do is write up the ad brief, spelling out what they want people to think, and sign the checks.

Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, in handing down a dissenting decision, raised the prospect of corporations being given the vote. Since, after all, they are people now. We might as well. A single vote is nothing compared to what they’ll do by bringing their wealth to mass persuasive political advertising.

It’s interesting to note how corporations get to pick and choose the good parts of being a person. They can own property but can’t go to prison. They can sue you into bankruptcy, which you have to live with for the rest of your life, but if you win a big case against them, you get nothing while they reconstitute their assets and arise, Phoenix-like, under a new name. If you misbehave, you are personally responsible; a corporation jettisons a minor component it says was to blame. There is no ending them. This is the kind of personhood you would choose, if you could. It’s what happens when people making laws about corporations are themselves beholden to corporations.

It’s not evil, exactly. It’s just everyone doing their jobs. It’s just the way the system works: the system that is increasingly designed by lawnmowers.

Enjoyment of cake and ice-cream spoiled by fear of running out of ice-cream before cake, or vice versa.

Enjoyment of cake and ice-cream spoiled by fear of running out of ice-cream before cake, or vice versa.

"Daddy I wanted to show you how good I was at drawing." http://yfrog.com/1e2fyej

"Daddy I wanted to show you how good I was at drawing." http://yfrog.com/1e2fyej

A Better Max

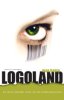

![]() Lately my Google Alert emails have become polluted with other Max

Barrys. I guess I knew it had to happen. I couldn’t have the web

to myself forever. But all of a sudden there are

three of us. The first guy to show up was okay.

He

writes about NFL. I gather that’s some kind of football. Not

the

good kind. But still. I was

just glad he was doing something. I didn’t want some whiny,

self-obsessed blogger Max Barry confusing everybody. I have that

base covered.

Lately my Google Alert emails have become polluted with other Max

Barrys. I guess I knew it had to happen. I couldn’t have the web

to myself forever. But all of a sudden there are

three of us. The first guy to show up was okay.

He

writes about NFL. I gather that’s some kind of football. Not

the

good kind. But still. I was

just glad he was doing something. I didn’t want some whiny,

self-obsessed blogger Max Barry confusing everybody. I have that

base covered.

But now this third guy. I’ve been worried about the wrong thing. Because this Max Barry, he’s better-looking than me. He models. He’s younger. More hair. I guess that goes without saying. But really: tons of hair. He cooks. Plays tennis semi-professionally. Works as a personal trainer. Posts workouts-of-the-day to his website. Workout-of-the-days? Whatever. He’s a god, is my point. A toned, buffed, let-me-whip-you-up-a-filet-mignon god. He makes me look like crap.

At this point I haven’t decided whether to break into his house in the middle of the night and stab him or become fast friends and use him as my body double for TV interviews. That’s a decision for the new year.

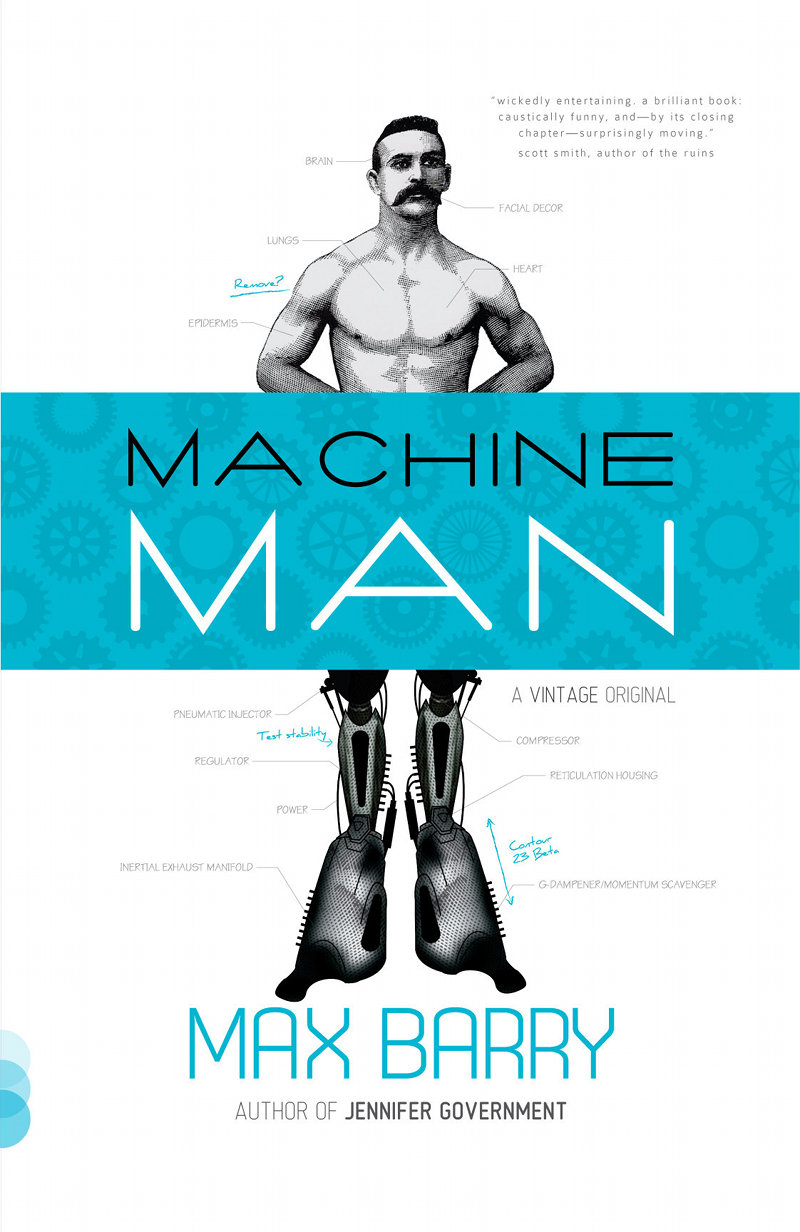

Speaking of which! That’s it from me for 2009. Thank you so much to everyone who cared enough to follow what I’m doing this year. Double thanks to everyone who made this the year of Machine Man. Triple—wait, this is getting ridiculous. But thank you, thank you to those who emailed me feedback on the serial, because that is incredibly helpful as I turn this thing into a novel.

I hope your year was a good one, and your next is better. And may I leave you with this: my daughter Finlay’s first ever appearance on stage, at her four-year-old ballet concert. They are dressed as kangaroos, if you’re wondering. This was one of the most terrifyingly beautiful moments of my life. I’m not talking about the dancing. I’m talking about what happened next.

♫ "I'm trying to find the words to descriiibe this giirrrl without being disrespectful… damn, you's a sexy bitch." Keep trying, David.

♫ "I'm trying to find the words to descriiibe this giirrrl without being disrespectful… damn, you's a sexy bitch." Keep trying, David.

It’s Not Me, It’s You

I’ve written more bad fiction than you’ve read. I’m serious. I’ve done a hundred or so drafts of nine or ten manuscripts, and let’s not even start on the shorter stuff. Read one of my books? Think it could have been better? Well that’s what they published. That was polished.

After a decade of wrangling paragraphs for a living, I have decided: it’s always the book’s fault. When your scene won’t quite come together, your novel idea won’t stay interesting, your main character refuses to fill out: it’s not because you lack talent. It’s because your idea is stupid. You’re trying to push shit uphill. And you may be a good shit-pusher, with a range of clever and effective shit-pushing techniques, but still: it’s going to be hard, frustrating, and ultimately you’ll discover you still don’t have your shit together.

I used to believe that an author needed an iron will. Discipline, to forge through the bitter dark and emerge clutching a tattered, tear-stained first draft. Now I think that’s a good way to lose nine months on a bad idea. Because if you have any skill as a word-slinger, you can make a bad idea sound okay. Not brilliant. But mildly interesting, at least for a while. Keep pushing that shit, though, and depression sets in. That’s when you think: I’m not good enough. Or: If I were more disciplined I’d finish this. Or: I can’t write.

Sure you can. You just can’t write this and stay interested, because it’s a stupid idea. It’s predictable. It’s been done. It had one intriguing aspect and you tapped that out within the first three pages. You don’t want to write this because your body is bone-bored of it.

A good idea excites you. It makes each day of writing a little joy. A good idea, when you peel it, has more good ideas inside. It makes you feel clever. It doesn’t need to be articulated. It might sound silly when you try to explain it. (Don’t try to explain it.) But you know there’s something there. It pulls you to the keyboard. It spills words from your fingertips. Some days, you lose your grip; you wander from the path and lose sight of where you were. But a good idea calls out to you.

A while ago I had The Block. The way I got out of it was to write a page of something new every day. The first week, I flushed out a lot of ideas that had been humming around the back of my brain, promising me they were brilliant. They weren’t. I captured them one page at a time and set them aside. The second week I wrote two things that were kind of interesting. Not very interesting. But not abominations, either. It was possible to imagine that in some alternate universe of very low standards, they could become novels. Not popular novels. But still.

The third week, I wrote something interesting. And I discovered I could write. That the reason I’d been stuck wasn’t because I’d forgotten where the keys were. It was because the story I was trying to make work sucked.

So that’s my advice to anyone mired in a story. Don’t blame yourself. You’re great. It’s just that stupid idea.

That Screaming Sound In Your Ears is Feedback

![]()

So I finished Machine Man. And I want to stay all cool and authory

about it, but honestly, I feel a little heartbroken. I think because when I tap out

THE END on a regular novel first draft, it means I finally have something I

can show people. But Machine Man wasn’t a regular first draft: it

was an experience, me posting one page at a time and checking the next morning

to see what people thought. That was freaking wonderful—terrifyingly wonderful—and now it’s over, I already miss it.

So I finished Machine Man. And I want to stay all cool and authory

about it, but honestly, I feel a little heartbroken. I think because when I tap out

THE END on a regular novel first draft, it means I finally have something I

can show people. But Machine Man wasn’t a regular first draft: it

was an experience, me posting one page at a time and checking the next morning

to see what people thought. That was freaking wonderful—terrifyingly wonderful—and now it’s over, I already miss it.

I think I will need to do this again. This, or something like it.

But my next step is turning the serial into a novel. Every first draft can be better; my first drafts can be a lot better. If you read this serial—even if you only read some of it—I would love to know what you thought. I usually distribute my first drafts to ten or twelve early readers. This time there are 600 of you, another three or four thousand in the free feeds. As a feedback junkie, this makes me trembly and excited.

If you’ve got an opinion, please let me hear it. I want nothing more than to make my stories as strong as they can be, and I need to figure out how this book reads to someone who hasn’t written it. So please help me: post a comment. Or, if you’d prefer to keep it private, email me.

I tell all my early readers: I’m after what you felt. Please don’t think you need to be a literary critic. Don’t try to imagine what other people might like. Above all, don’t hold back because you can’t think how to justify what the book made you feel. Figuring out why you had a particular reaction and what to do about it, that’s my job. I can do that. What I can’t do is read my own book for the first time. The closest I can get is hearing you describe how you felt when you read it.

Please do tell me what you liked and what you didn’t. I’m looking for flaws, but part of figuring out what to improve is understanding where its heart is. Also, I tend to assume that anything an early reader doesn’t mention she didn’t care terribly much about, so it’s a candidate for the ax. If you stopped reading at some point, please tell me where. If you’re partway through, please share your thoughts so far. If you don’t know what the hell I’m talking about with feelings versus literary criticism and all that, please comment anyway. One-sentence thoughts are fine. I can’t get too much feedback. Please. Tell me.

Thanksgiving: the day each year I spend wondering why no-one from the US is responding to my emails.

Thanksgiving: the day each year I spend wondering why no-one from the US is responding to my emails.

A Business Fable

![]() Once upon a time a boy went to business school. The boy was not sure he wanted to go into business, because what he most loved was writing stories about aliens and monsters and girls who did not love him back. But he knew he could not hope to earn a living from such stories, so business school it was.

Once upon a time a boy went to business school. The boy was not sure he wanted to go into business, because what he most loved was writing stories about aliens and monsters and girls who did not love him back. But he knew he could not hope to earn a living from such stories, so business school it was.

The boy learned many interesting things, until he began to think perhaps business was for him after all. One day, he attended a class in which students were divided into groups and asked by the lecturer to solve the following puzzle:

“A man buys a horse for $400. He feeds it, trains it, and sells it to a racetrack manager for $500. However, soon he regrets his decision, and asks the racetrack manager if he can have the horse back. The racetrack manager, being a good capitalist, asks for $700. The man objects, seeing no reason why the horse should be worth so much more than the day before, but eventually he relents and accepts the loss. Some years later, he finally sells the horse to neighbor for $800. Question: What is his total profit or loss?”

The boy’s group began to discuss this puzzle. The boy thought the solution was fairly obvious: the man bought and sold the horse twice, making $100 profit each time. However, his teammates were seduced by the puzzle’s suggestion of a loss, and insisted this be accounted for. They thought the man broke even.

The boy tried to explain his reasoning a different way. He added up the man’s outlays and revenues, showing the difference was $200. The group agreed, but insisted this was then canceled out by the loss. The boy tried again. “Imagine it’s not the same horse,” he said. “The man buys and sells one horse, then buys and sells a second horse.” The debate became heated. There was no second horse, the group insisted. There was one horse, and the man broke even.

After a few minutes, the lecturer halted the exercise and asked each group for its verdict. Only unanimous decisions would be accepted. Every other group in the class declared their belief that the man broke even. The boy’s group hissed at him to bow to the majority opinion, but he could not bring himself to do it. They informed the lecturer that they could not agree.

The answer, said the lecturer, was that the man made $200 profit. However, the exercise was not about that. It was designed to test teamwork. He had observed most groups working effectively: establishing leadership roles, managing divergent opinion, and finding common ground to reach a shared solution. The boy’s team, however, was a textbook example of failure: it had allowed a disruptive element to block them from consensus. It was then that the boy decided business was probably not for him.

Behold: the terrifying security powers of SMOKE. http://yfrog.com/4gb0hj

Behold: the terrifying security powers of SMOKE. http://yfrog.com/4gb0hj

Acquired a cat. http://yfrog.com/ja5twj

Acquired a cat. http://yfrog.com/ja5twj

Uploaded new design to http://maxbarry.com. Much like old design, only with HUGE PICTURE OF MY MUG beaming down, Mao-like.

Uploaded new design to http://maxbarry.com. Much like old design, only with HUGE PICTURE OF MY MUG beaming down, Mao-like.

Hollywood Wants a Piece of Charlie

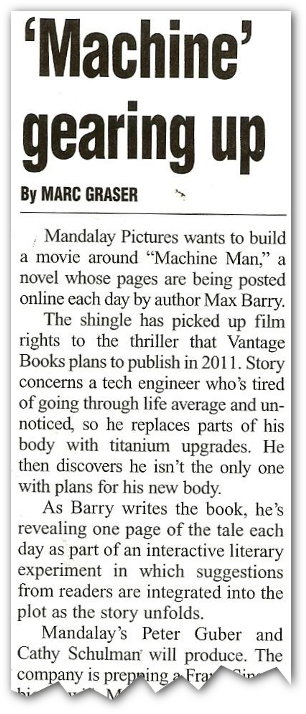

![]()

You

were in Hollywood trade Bible

Variety. No,

really. True, you weren’t the main focus. The main focus was

OH BY THE WAY

THEY’RE MAKING A MACHINE MAN MOVIE.

You

were in Hollywood trade Bible

Variety. No,

really. True, you weren’t the main focus. The main focus was

OH BY THE WAY

THEY’RE MAKING A MACHINE MAN MOVIE.

Well, when I say “making,” I mean “it’s in development.” And as we have learned, sometimes painfully, movies in development often do not make it out of development, at least not in our lifetimes. But still! This is a pretty amazing thing for a not-quite-finished experiment in fiction.

“They” in this case is Mandalay Pictures, who do actually get stuff made, and who I think get this concept particularly well. I’m not saying they’re self-mutilators. I have no proof of that. Let’s just say that if you were, I think they’d be sympathetic.

So Marc Graser of Variety reported this, and look what he said!

…suggestions from readers are integrated into the plot as the story unfolds.

I’m not sure I want that in print. That seems like the kind of thing that could lead to lawsuits. But, well, it’s true: you guys post comments, I read them, and that affects what I write the next day. So there you go. We have a film deal.

I have to mention (again) my Machine Man muse/tormentor M.I. Minter, the guy who essentially provoked me into doing this, because his response to this latest development was:

It’s amazing the fantastic things that happen when you regularly produce work.

I’m starting to suspect that M.I. Minter will make one hell of a Daddy one day. He has a knack of delivering delicious, crunchy praise with a chewy, you-can-do-even-better center.

52 comments

52 comments