Metrics

![]() I can’t believe people keep getting surprised by Facebook. They use your personal information to make money. They have no financial interest in your privacy but a huge one in eroding it. It’s been like that since forever.

I saw a guy post that he was “continuously shocked” by Facebook’s privacy invasions. How can you be continuously shocked? At some point, don’t you realize this is simply the way it is?

I can’t believe people keep getting surprised by Facebook. They use your personal information to make money. They have no financial interest in your privacy but a huge one in eroding it. It’s been like that since forever.

I saw a guy post that he was “continuously shocked” by Facebook’s privacy invasions. How can you be continuously shocked? At some point, don’t you realize this is simply the way it is?

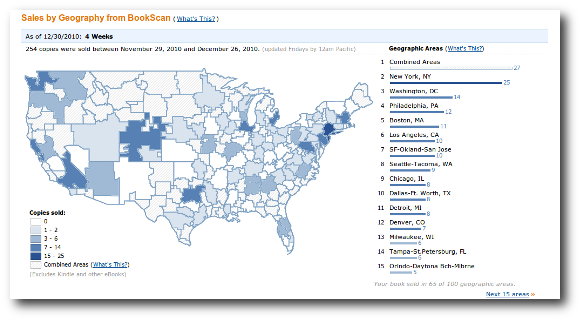

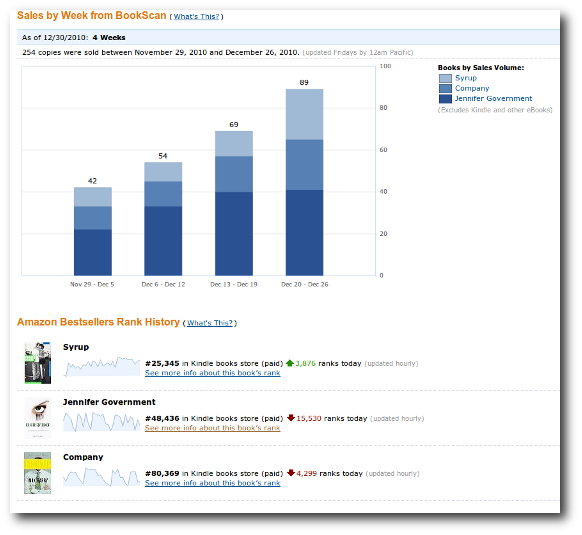

Anyway. I didn’t mean to write about Facebook. I meant to write about technology. I’m allowed to do more geeky blogs this year, because I have a book coming out about cyborgs. So check this out. This is Amazon’s AuthorCentral Metrics. It shows how many of my books are being sold and where:

This is a free service to authors. There’s also a history:

Last time I had a book published, I had to wait ten months for a royalty statement to find out whether anyone bought it. Machine Man I’ll be able to follow in almost-real-time. I’m not sure whether that’s useful for anything, other than satisfying impatience. But still.

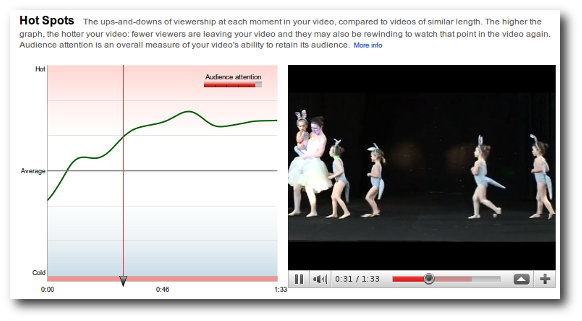

Here’s what I really want. The screenshot below is from YouTube. A while back I uploaded a video of my daughter being incredibly cute. YouTube tracks whether people watch all the way to the end, and, if not, where they give up, to create a graph of “attention.”

I want this for books. I would kill for it. I want to know at which point people are putting my books down, or giving up on them, so I can write better ones next time. I want to know which parts they re-read. It’s got to be possible now, with e-readers. Get on that, Amazon.

The Lawnmower People

![]() I was all set to do a blog about how using Windows is like growing evil tomatoes,

then American corporations became real people. They’ve been people for a while,

of course: they have the right to own things and sue you and claim they’ve been

defamed. Your chair can’t do that. A corporation can, because it’s a person.

I was all set to do a blog about how using Windows is like growing evil tomatoes,

then American corporations became real people. They’ve been people for a while,

of course: they have the right to own things and sue you and claim they’ve been

defamed. Your chair can’t do that. A corporation can, because it’s a person.

But they weren’t enough of a person, apparently, so now they have First Amendment rights. In particular, they have the right to spend as much money as they like on political advertising: airing ads in favor of anti-regulation candidates over pro-regulation ones, for example.

I find it helpful to think of corporations as lawnmowers. Lawnmowers are good at cutting grass. It’s all they want to do. They’re not very concerned about what gets in the way of cutting grass. If, for example, we discover that one of the lawnmowers sometimes kills people, the lawnmower would rather pretend there isn’t a problem than stop mowing lawns. It seems callous to us. But you have to remember, it’s not a person. It’s a lawnmower.

Corporations pursue profit; the fewer people watching, the more ruthlessly they do it. It’s not coincidence that Apple is a relatively nice corporation and Halliburton is not. It’s not that Apple was raised right while Halliburton had a distant father. It’s that Apple’s profits depend more heavily on consumer opinion. It can’t make money unless it’s likable, so it is.

I think lawnmowers are useful. I don’t want to get rid of them. But I very much want to keep them on the lawns.

The Supreme Court has let them into homes: now the lawnmowers will speak to us through TV, radio, internet, print, and tell us who to vote for. That might not seem like a problem. After all, you are a smart person. You’re probably not persuaded by advertising. The thing is, everyone thinks that, and advertising is an $600 billion industry. Someone, somewhere is getting $600 billion worth of persuasion.

It’s pretty obvious that lawnmowers will back pro-lawnmower candidates. They are functionally and legally prevented from doing anything else. In fact, now that the opportunity exists, lawnmowers are compelled to exploit it.

Honestly, I had started to think that the world of Jennifer Government was getting far-fetched. It seemed like corporations were not overpowering the government at all; instead, the two were slowly merging into a govern-corp megabeast. But this changes things. Until now, corporate lobbyists have essentially stood in opposition to voters: politicians wanted lobbyist money, but resisted giving in too much for fear of being punished at the ballot box. Now corporations can work it both ways. They can buy off the politicians and sell the voters on why that’s A-OK. They won’t have to come up with the media messages themselves. That’s a job for the ad agency. All they’ll do is write up the ad brief, spelling out what they want people to think, and sign the checks.

Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, in handing down a dissenting decision, raised the prospect of corporations being given the vote. Since, after all, they are people now. We might as well. A single vote is nothing compared to what they’ll do by bringing their wealth to mass persuasive political advertising.

It’s interesting to note how corporations get to pick and choose the good parts of being a person. They can own property but can’t go to prison. They can sue you into bankruptcy, which you have to live with for the rest of your life, but if you win a big case against them, you get nothing while they reconstitute their assets and arise, Phoenix-like, under a new name. If you misbehave, you are personally responsible; a corporation jettisons a minor component it says was to blame. There is no ending them. This is the kind of personhood you would choose, if you could. It’s what happens when people making laws about corporations are themselves beholden to corporations.

It’s not evil, exactly. It’s just everyone doing their jobs. It’s just the way the system works: the system that is increasingly designed by lawnmowers.

Big Brother Is Actually Not Watching You At All

![]()

Nine

girls were trapped in a big house in Turkey, their every move filmed

for the titalation of their captors. Not recently. This was about a month ago. I’m

only mentioning it now because a month ago

my brain wasn’t working. Back then,

I just thought, “That… irony… blog.” That’s as far as I got. But I’m feeling better now,

thanks for asking.

Nine

girls were trapped in a big house in Turkey, their every move filmed

for the titalation of their captors. Not recently. This was about a month ago. I’m

only mentioning it now because a month ago

my brain wasn’t working. Back then,

I just thought, “That… irony… blog.” That’s as far as I got. But I’m feeling better now,

thanks for asking.

So the interesting part is that the girls thought they were on Big Brother. According to reports:

…the women were not abused or harassed sexually, but were told to fight each other, to wear bikinis, and to dance by the villa’s pool.

Upon discovering this was not for a national TV audience but just a couple of horny old men who owned the house (I’m guessing), the girls reacted badly. Apparently they demanded to be released. But they’d signed contracts, promising to stay for at least two months, and the contracts had some pretty serious penalty clauses: tens of thousands of dollars if the girls left early. I guess you call that a pay or play deal.

The girls took the position they’d been duped, so they were essentially being kidnapped. When the police found out, they agreed.

Me, I’m not so sure. It seems the girls’ main objection is that while they were wearing bikinis, dancing by the pool, and talking about their most embarrassing sexual experiences (I’m guessing), not enough people were watching. These degrading, exploitative acts they were pressured to perform, they weren’t broadcast on prime-time. The problem was there was no fame. The mother of one of the girls said:

We were not after the money but we thought our daughter could have the chance of becoming famous if she took part in the contest. But they have duped us all.

Being watched by two sleazy guys wasn’t enough. If it were millions of sleazy guys, that would be okay. But two? That’s sick.

Zombies Are For Grown-Ups: Why Banning Video Games Makes Them More Violent

![]()

I’m

a parent. I also like to slay zombies. Lately, my wife and I have spent

nights side-by-side, mowing down hordes of gibbering undead with automatic

weapons. Sometimes we blow them up with pipe bombs, or set them on fire.

We don’t go looking for them. They rush at us out of darkened city alleys.

They break through doors. It’s us or them.

I’m

a parent. I also like to slay zombies. Lately, my wife and I have spent

nights side-by-side, mowing down hordes of gibbering undead with automatic

weapons. Sometimes we blow them up with pipe bombs, or set them on fire.

We don’t go looking for them. They rush at us out of darkened city alleys.

They break through doors. It’s us or them.

I’m talking of course about the computer game Left 4 Dead. It has a sequel, due out next month, which looks similar—so similar, in fact, there is a protest by Left 4 Dead fans that it should be a free update, not a new full-price game. The main difference seems to be that it has hand weapons, inviting players to bludgeon zombies with baseball bats, chop them up with axes, and dismember them with chainsaws.

This was too much for the Australian Classifications Board, which ruled that the game’s “unrelenting violence” was “unsuitable for a minor to see or play.” Of particular concern were those hand weapons, which:

…cause copious amounts of blood spray and splatter, decapitations and limb dismemberment, as well as locational damage where contact is made to the enemy which may reveal skeletal bits and gore.

Australia has no adults-only classification for video games: all games must be qualify for MA15+ or lower to be allowed on sale. (We are, apparently, the only developed democracy in the world without an 18+ category for games.) The chief advocate of this position is South Australian attorney general Michael Atkinson, who responded to the banning of Left 4 Dead 2 by saying: “It certainly does restrict choice to a small degree, but that is the price of keeping this material from children and vulnerable adults. In my view, the small sacrifice is worth it.”

I’m not quite sure what he means by “vulnerable adults.” Possibly Atkinson thinks there is a class of grown-ups who really aren’t: who should be treated like children their entire lives. Possibly this class includes adults who like to play video games.

But that’s not the point. The point is what happened next: the game developer, like other developers before it, deleted some of the gorier parts and resubmitted it. The Australian Classifications Board noted that “large and frequent blood splatters are seen,” but now “dead bodies and blood splatter disappear as they touch the ground.” You can still rip zombies to pieces with a chainsaw, but “no wound detail is shown.” It was awarded an MA15+ classification (meaning 14 year olds and younger require a guardian present), tagged: “Strong bloody violence.”

Instead of Australia having a violent, bloody computer game restricted to adults, it will have a violent, not-quite-as-bloody game on sale to children. This is the effect of our law: to take content that was designed for adults and tweak it until it scrapes under the MA15+ bar. We’re making available to children material they would not otherwise see, clustered at the extreme end of what is acceptable.

Left 4 Dead comes with a developers’ commentary audio track, like a DVD. (The industry has grown up: popular titles cost as much to produce as blockbuster films, are promoted as heavily, and generate as much revenue, or more.) You can hear the designers describe how they used sound, light, and dramatic techniques to create an atmosphere of dread. How each zombie has a unique face and behavior: sometimes they wander around, or sit, or put their faces in their hands and sob. When they die, their flailing movements are based on a motion-captured stunt man, to look more realistic.

We need to worry less about 15-year-olds seeing “wound detail” and more about immersing them in an environment of unmitigated horror. The most shocking films and books are not merely graphic, they are suggestive. Even the most explicit horror movies chill primarily not because of what they depict, but what they might. Any storyteller knows: the monster is scarier before it’s revealed. There is more to terror than blood.

So far this debate has been framed as an argument between protecting children and upholding adults’ freedom of choice. We’re doing neither.

Risk

(Link: Max Barry On Risk, ABC Fora or via The Monthly.)

Actually, first that’s Julian Morrow, introducing me. I feel I should point this out because you don’t see me very often, and even to me, all thirty-something white guys with no hair look the same.

Australians with digital TV can catch this on ABC2: an extract (I think) this Sunday at 6pm, and the full thing on Thursday at 5:30pm.

This lecture was for Sydney PEN’s Voices, and delivered at the State Library in Sydney on July 15, 2009. It’s not the kind of thing I usually do. In fact, it’s probably the first time I’ve been asked to write something serious since I became a novelist. It was a cathartic experience: I’m deeply grateful to have had the opportunity to do it, and to the audience on the night for being so supportive.

15 comments

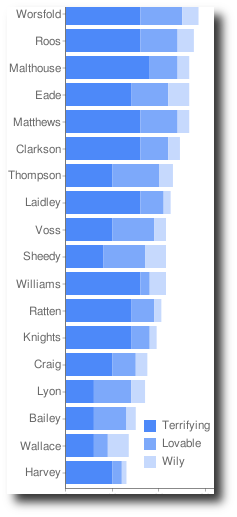

15 comments Because

I woke at 5AM this morning and couldn’t go back to sleep, I decided to rate

AFL coaches on those three dimensions. I scored a coach highly on

Terrifying if he is combative in interviews, physically intimidating, and

generally looks seconds away from pushing somebody’s head

through a wall. He scored Lovable points if he is the sort of bloke I

would want to share a beer with or invite home for dinner. And I awarded

Wily points if he is clever and tactical, both on match day and in the media.

Because

I woke at 5AM this morning and couldn’t go back to sleep, I decided to rate

AFL coaches on those three dimensions. I scored a coach highly on

Terrifying if he is combative in interviews, physically intimidating, and

generally looks seconds away from pushing somebody’s head

through a wall. He scored Lovable points if he is the sort of bloke I

would want to share a beer with or invite home for dinner. And I awarded

Wily points if he is clever and tactical, both on match day and in the media.