Australia gets closer

![]() On September 11, 2001, the city of Melbourne, Australia evacuated its World Trade Center.

This is a short building on the banks of the Yarra River, a short distance from Melbourne’s central business district, a little over ten thousand miles from New York. It used to have a casino; before that, it hosted an exhibition of waxworks from Madam Tussaud’s. If you ran a line from Ground Zero in Lower Manhattan through the center of the Earth, you would exit the planet not so very far from here—closer, certainly, to Australia than to any other country in the world.

On September 11, 2001, the city of Melbourne, Australia evacuated its World Trade Center.

This is a short building on the banks of the Yarra River, a short distance from Melbourne’s central business district, a little over ten thousand miles from New York. It used to have a casino; before that, it hosted an exhibition of waxworks from Madam Tussaud’s. If you ran a line from Ground Zero in Lower Manhattan through the center of the Earth, you would exit the planet not so very far from here—closer, certainly, to Australia than to any other country in the world.

Australia is a long way from everywhere. A flight to Sydney takes 15 hours from Los Angeles, 21 hours from London, 14 hours from Johannesburg, and 10 hours from Tokyo. There is no stopping off in Australia on the way to somewhere else, unless you’re headed to Antarctica. You can’t take in Australia as a side-trip while visiting somewhere else nearby. It is an island continent that you reach only by making it your ultimate destination and exerting a concerted effort.

This isolation is the core of Australia’s identity: it is the reason the country has an aboriginal population that existed undisturbed for 40,000 years, and some of the world’s strangest and most inimitable flora and fauna, and why, indeed, it was chosen to be a penal colony by the British in 1788. It is a place you go to be removed from the world.

But on 9/11, terrorists were attacking World Trade Centers, so Melbourne evacuated hers. This didn’t seem silly at the time; that day made all horrors plausible. No precaution was too extreme when yesterday it had been inconceivable that terrorists might take thousands of lives in New York and across the US, and today it had happened. So for a while, Australia forgot it wasn’t part of the world. “We are all Americans,” Australians said on 9/11—September 12, actually, on antipodean time, since Australia is so far away it is usually a different day altogether. And we meant it: we were deeply shocked to see acts of foreign terrorism, always previously associated with unfamiliar people in unfamiliar places, happening somewhere Over There, become suddenly intimate and recognizable.

Over time, though, the War on Terror became the War on Iraq, and the American flags on TV reminded us that although 9/11 affected the Western world, at its most pointed and personal, it was an American story. Australia, as usual, was watching from afar. We sent troops to Afghanistan and to Iraq, maintaining solidarity with our American cousins, but ultimately, we came to realize that the US was Over There, too.

In 2002, 88 Australians were killed by a radical Islamist group bombing on the Indonesian island of Bali, a popular holiday destination. Bali is a mere six hours from Sydney, and only two and a half from Darwin, the closest Australian city. It was a traumatic event, but again, it wasn’t quite Here. More recently, there have been police terror sweeps in Australian cities, with arrests made and, apparently, plots foiled. The federal government warned us that groups had developed with the motivation and ability to carry out local attacks.

You live a charmed life in Australia. The streets are safe; the weather is terrific; the people are friendly. The ocean keeps everything out. Or, at least, slows it down. We complain about that, when a car costs thirty thousand dollars, or a TV show won’t hit our screens right away, but it’s the ocean that has allowed Australia to stay Australia in the face of relentless globalization. It’s given us more than a decade in which to rethink our ideas on society and our way of life, and the trade-offs between freedom and security we’re willing to make, without having to do so in the immediate aftermath of a national tragedy.

On Monday, a man with a gun took hostages in the middle of Sydney in what he claimed to be an attack on Australia by the Islamic State. A self-described cleric with a history of antagonism toward Australian military involvement in Afghanistan, he was, by all reports, a dangerous loner rather than a member of an organized terrorist group. By the time the siege was over, two hostages were dead.

If this man had claimed to be acting for some other cause—disgruntlement at the tax code, or the high price of cars—we wouldn’t call it terrorism. We would call it what it is: a lunatic with a gun. But that would overlook the deeper trend, which is that Australia’s oceans are shrinking. Today technology allows a man to be more connected to militant extremists across the globe—in spirit, if nothing else—than he was to his neighbors in Bexley North. He can latch on to toxic ideas from the other side of the globe and bring them into Sydney, feeling he is part of a global cause.

Whether we call it a siege or terrorism, this is something that used to happen Over There. And now it’s here. It wasn’t unexpected, and arrived more benignly than it could have, and today the country will get on with business as usual. But life is becoming a little less charmed. We are no longer so far away.

Dear Pirates: This is How to Help

![]() Sometimes people pirate my stuff. Then sometimes they write to tell me they

pirated my stuff, because they feel kind of bad about it, and wonder if they

can pay me somehow. (Except one time when a guy said he’d pirated a compilation

of “100 Great E-Books” and he just wanted to let me know I was in it, as a compliment.

A kind of compliment.)

Sometimes people pirate my stuff. Then sometimes they write to tell me they

pirated my stuff, because they feel kind of bad about it, and wonder if they

can pay me somehow. (Except one time when a guy said he’d pirated a compilation

of “100 Great E-Books” and he just wanted to let me know I was in it, as a compliment.

A kind of compliment.)

For example:

Now I had read your latest blog post about the movie the other day saying it had been released on iTunes and some cable websites, so <pirate pirate pirate>, so right now Syrup is 42% completed, and with my guilt (and procrastination, as I’m still typing this email) growing with every percentage, I thought to ask your opinion.

I’ve been looking forward to the Syrup movie since I read the book and thought “This would make a damn good movie!”, and then came the first rumours or it actually becoming one, so of course I want to support the production company and in turn future movies/series (I’m trying not to get my hopes up for Jennifer Government), but I can’t wait.

Would there be a PayPal donation link I can use to throw you the cost of a movie ticket? Or should I watch it now and when it eventually hits theatres and see you as a waiter on the big screen? Buy the DVD?

What, as the writer of the source material for a movie, do you think is the most beneficial method (to whoever you think deserves it. I of course, thought you) of paying for my viewing pleasure?

The general answer is that you should tell people you watched it. Or that you read it, if it’s a book. You should tweet, “Just finished <whatever>, highly recommended,” assuming you liked it, or “Just finished <whatever>” if you didn’t. Or post on Facebook. Or write a nice review somewhere. If you do this, you are all square in my eyes. In fact, I’d bet most artists and content creators feel the same way. Because the major problem they face isn’t that people pirate their work; it’s that nobody knows they exist.

Getting people talking is massive. Enormous amounts of time and energy are poured into getting people talking about every single book and film and song ever released. You, talking about a book/film/song, is really valuable. I can’t emphasize that enough. It can galvanize all kinds of great outcomes.

A Pirate Tip Jar (Jaarrrrr), on the other hand, would be a bad move. Lots of people work on books and films, not just me; even on a novel, I’m due no more than 15% of what you pay. I don’t want anyone thinking they can cut those people out and pay me directly. Also, I suspect the number of people who say they’d love to pay for X if only there were a more convenient way of doing so is far greater than the number of people who would actually pay. I mean, it’s a nice sentiment. But we generally pay for things because we have to. That’s just how it works.

So instead of wishing you could tip an artist for something you pirated, talk about it. That’s good for everyone involved. If you have nothing good to say, even a simple mention is helpful. Not a bad mention. That’s not helpful. But the difference between pirating something and saying nothing vs. pirating something and mentioning it to other people is really, really huge.

Of course, piracy is kind of wrong. I feel I need to say that explicitly. It’s kind of wrong because people who create something like a book or movie or song should be able to decide if and how they’ll sell it. Just because it’s more than you’d like to pay doesn’t mean it’s fair to pirate; everything is more than you’d like to pay. If Justin Timberlake made a CD and priced it at a thousand dollars a copy, such would be his right.

But it would be pretty silly of Justin to think people wouldn’t pirate that. Especially fans, and especially if that CD was only released in one country at a time and didn’t work on everyone’s players. I would be surprised if Justin wasn’t fully aware that this situation would provoke quite a lot of piracy. I have no idea why I’m using Justin Timberlake as an example. That just happened. But what I’m saying is that while piracy is generally bad for artists, and we want you to buy real books/tickets/MP3s/downloads, I recognize that piracy happens sometimes anyway. And if it happened to you, and you want to say thanks, you can do a lot of good by spreading the word.

Revenge of the Rats

![]()

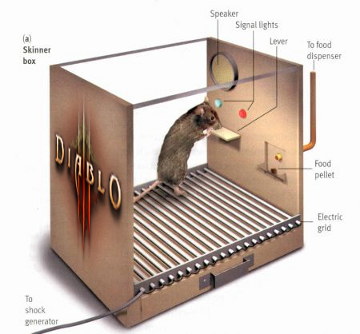

In

1957, a psychologist named B. F. Skinner decided to see what happened

when you put a rat in a cage with a lever that made food come out.

He discovered that if the food came out whenever the lever was pushed, the rat

would settle into a healthy work-life balance of pushing levers and running

hamster wheels. But if the lever only delivered food sometimes—if

it randomly might or might not—the rat would work that lever like there was

no tomorrow.

In

1957, a psychologist named B. F. Skinner decided to see what happened

when you put a rat in a cage with a lever that made food come out.

He discovered that if the food came out whenever the lever was pushed, the rat

would settle into a healthy work-life balance of pushing levers and running

hamster wheels. But if the lever only delivered food sometimes—if

it randomly might or might not—the rat would work that lever like there was

no tomorrow.

This research underpinned much development of poker machines and gaming. Now Diablo III reveals what happens when the rats have internet access: they bitch about drop rates.

The Diablo series of games are simple: you run through dungeons, hit monsters, and collect the items that fall out. Usually the items are crappy, but sometimes, randomly, they’re awesome, and allow you to fight even more powerful monsters, which can randomly drop even more awesome items. The game ends when you starve to death in your apartment surrounded by empty soda cans.

Actually, that’s not true: there is an end-game. Your character can’t progress beyond level 60 and there’s a hard maximum to the potential quality of items. So there is a diminishing returns thing: early in the game, you find better items often, but as your equipment approaches the theoretical maximum, your odds of finding something better become decreasingly smaller.

Diablo III had a few problems when it launched, and there was much bitching on internet forums. A great deal of the bitching was about drop rates; that is, how likely food was to arrive when you pressed the lever. Players thought drop rates were too low, if you were wondering. They wanted food to come out more regularly. A very popular proposal, one mentioned in almost every discussion, no matter how relevant, was that more situations should deliver “a guaranteed rare,” a “rare” being a high-quality item. That is, instead of food only coming out sometimes when you pushed the lever, it would come out every time.

This feedback around drop rates was offered to the developers in the form of an unholy maelstrom of teenage-grade internet fury that raged for many weeks. Players railed against the bitterness of a life of inadequate drop rates, expressing their incomprehension that such stupidity should exist and turning viciously against their former idol, game designer Jay Wilson, who was now revealed not as a benevolent provider of sometimes-food but rather the very face of evil, Diablo himself, as it were, He Who Made The Lever Not Work Often Enough.

Some of the angst was understandable. Diablo III introduced an in-game Auction House, which meant that instead of throwing your old items away as you found new ones, you could sell them to other players for gold. The marketplace being virtual and therefore operating with a degree of efficiency rarely seen in the real world, it was soon a lot easier to find good items on the Auction House than to go around hitting monsters hoping that one would randomly fall out. This in turn allowed players to obtain items approaching the hard maximum quite quickly after starting the game, and rendering their chances of thereafter seeing anything better randomly drop from a monster close to zero.

After sufficient buffeting, the developers decided to increase drop rates. They also created more “guaranteed rare” situations. This was very warmly received by the community. It wasn’t enough, though, and since then drop rates have been raised again, and “legendary” items radically overhauled to make them much better, i.e. more like food. At the same time, a new reward system was introduced called “Paragon Levels,” which periodically deliver such an enormous explosion of congratulation to the player that it almost feels sarcastic. This has quieted community angst, although at this point it’s hard to tell how many of them are left. I suspect a lot have stopped pushing the lever.

The interesting part about the rats who like to gamble is that they don’t do it for food. They don’t press the lever only as many times as required to deliver the same amount of food as when food delivery is guaranteed: they press it more often and more rapidly. They like to see if they can win. Although “like” could be the wrong word; it may be more accurate to say that the uncertainty creates stress, which they feel the need to resolve. I would imagine there are some pretty pissed-off rats, when they press the lever a bunch of times and still nothing happens. They would rage on the internet if they could. And they’d be justified, since it wasn’t their choice to get in the cage. Somebody put them there, who knew what would happen.

This Sentence is Already Too Long

![]() Blogs are dying. Not this blog. I mean in general. This blog’s

just fine. Okay, yes, it has been a little while since the last post,

but that’s just because I was busy writing. Well. Rewriting. It’s like

writing, only with less visible progress. With writing, you can

feel reasonably assured that what you put on the page is

better than what was there before. Not always! But mostly.

Rewriting, though, you can spend a good six hours on a scene,

sit back, and think, “Yep… that’s worse.”

Blogs are dying. Not this blog. I mean in general. This blog’s

just fine. Okay, yes, it has been a little while since the last post,

but that’s just because I was busy writing. Well. Rewriting. It’s like

writing, only with less visible progress. With writing, you can

feel reasonably assured that what you put on the page is

better than what was there before. Not always! But mostly.

Rewriting, though, you can spend a good six hours on a scene,

sit back, and think, “Yep… that’s worse.”

Anyway. Blogs are OUT. They’re too long. That’s the problem. No-one has the time for them. The middle is hollowing out. Everything is polarizing. We want things to be very. It doesn’t matter what. Whatever it is, only very. There’s no place for mid-length writing any more. There never was, of course. But blogs used to be short. Then Twitter. Now blogs are like One Day Cricket.*

But here we are! And it’s already been more than 140 characters. So let’s continue. This blog will summarize what I’ve been thinking about over the last few months, while I was busy making my new book not worse.

Sneaker riots. The first one or two were kind of shocking to me, like a thought come to life. The next few were disappointing, like repeated plot points. But now we’re at, what, the seventh Nike sneaker riot? When does it become less likely that they’re continually being surprised by this kind of thing happening and more likely that they’re deliberately engineering it? That’s just a question. I’m just wondering.

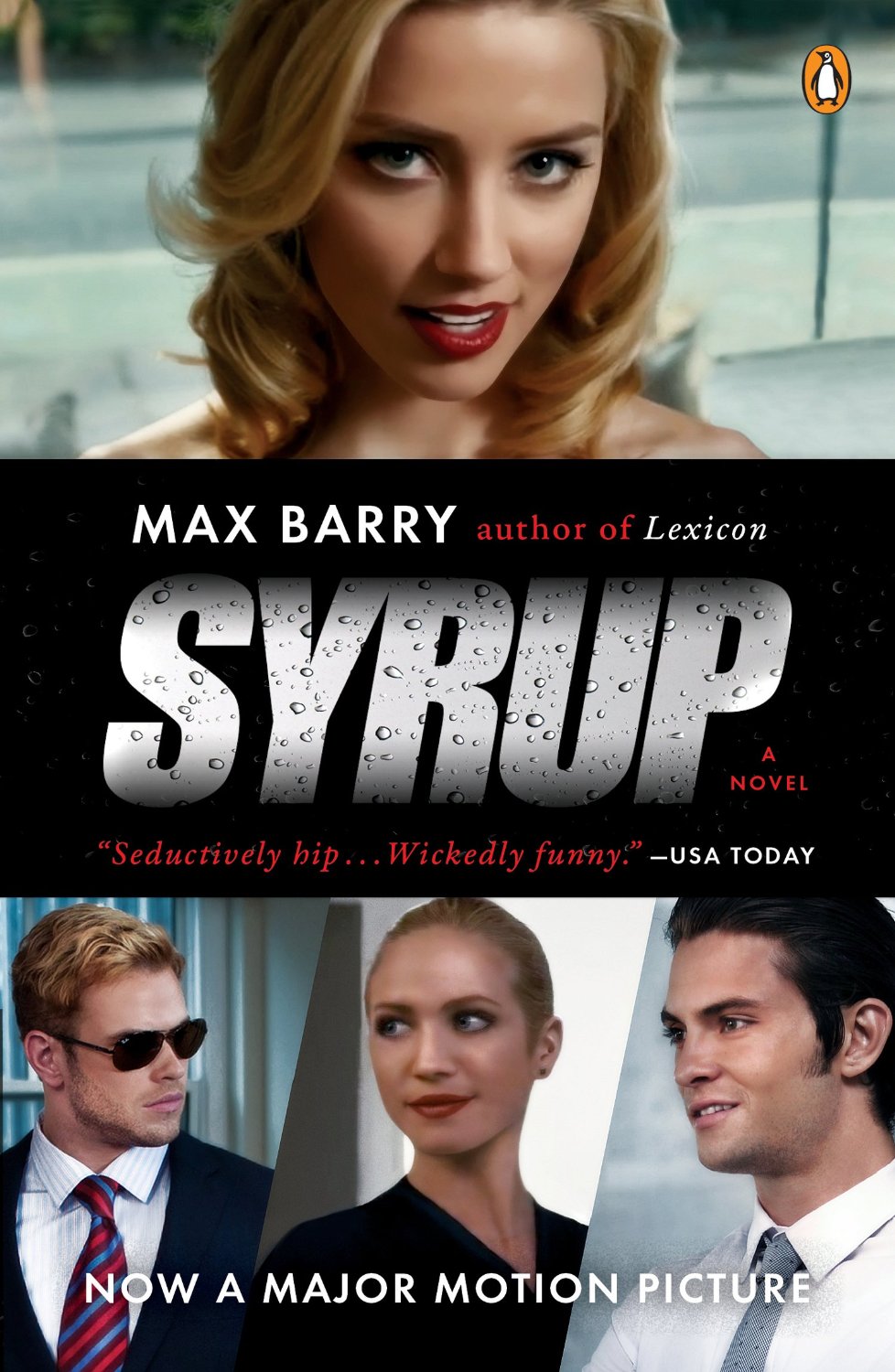

Syrup movie. Now in post-production. I have been shown a teaser-trailer thing and it is heartbreakingly beautiful. I’ve watched it three hundred times. I’m not joking. The only thing that sucks about the Syrup movie is I’m not allowed to tell you anything. But soon. Soon…

Privacy. This interests me because privacy is obviously very important for reasons nobody understands. Generally, there’s a much stronger incentive for companies and governments to want to know things about you than for you to keep your data private. That leads to an interesting place.

Persuasion. This is the most valuable skill in the world, right? People who are good at persuading others become rich and successful; people who are easily persuaded by others do not. But nobody really thinks about this. Very few people actually go out and learn how to be better at persuasion, or more aware of its forms. Why is that?

Also, the US as a culture is very advanced at soft persuasion (i.e. the forms of persuasion that don’t involve threats of bodily harm). It is great at selling stuff. We have the Internet and free access to vast stores of information but we’re still buying products with the cleverest ads, and electing politicians with the most reassuring voices. I wonder what happens if a culture becomes so good at persuasion that there is no longer an incentive to produce products that are just objectively good, as opposed to well-sold.

Privacy + Persuasion. It’s easier to persuade people if you know more about them. And if you can persuade them, you can get more information from them. That’s an interesting dynamic, too.

Piracy. But this is too depressing for now so I’ll blog about it later.

That’s a lot of Ps, for some reason.

(* This analogy works because even if you don’t know cricket, you know it is stupid and anachronistic.)

Dogs and Smurfs

![]() This has been a great year for male writers, with women shunted

aside for major prizes and all-new hand-wringing about why it is so.

Because, I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but male writers get taken

more seriously. Also, stories about men, even if written by women,

are considered mainstream, while stories about women are “women’s fiction.”

This despite the fact that women read more than men, and write

more, and are over-represented generally throughout publishing.

This has been a great year for male writers, with women shunted

aside for major prizes and all-new hand-wringing about why it is so.

Because, I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but male writers get taken

more seriously. Also, stories about men, even if written by women,

are considered mainstream, while stories about women are “women’s fiction.”

This despite the fact that women read more than men, and write

more, and are over-represented generally throughout publishing.

As the father of two girls, one aged five and one ten months, I know why. It’s because of dogs and Smurfs. I can’t understand why no-one else realizes this. I see these knotted-brow articles and the writers seem truly perplexed. Dogs and Smurfs: that’s the answer.

Let me walk you through it. We’ll start with dogs. I have written about this before, but to save you the click: people assume dogs are male. Listen out for it: you will find it’s true. To short-cut the process, visit the zoo, because when I say “dogs,” I really mean, “all animals except maybe cats.” The air of a zoo teems with “he.” I have stood in front of baboons with teats like missile launchers and heard adults exclaim to their children, “Look at him!” Once I saw an unsuspecting monkey taken from behind and there was a surprised silence from the crowd and then someone made a joke about sodomy. People assume animals are male. If you haven’t already noticed this, it’s only because it’s so pervasive. We also assume people are male, unless they’re doing something particularly feminine; you’ll usually say “him” about an unseen car driver, for example. But it’s ubiquitous in regard to animals.

Now, kids like animals. Kids really fucking like animals. Kids are little animal stalkers, fascinated by absolutely anything an animal does. They read books about animals. I just went through my daughter’s bookshelves, and they all have animals on the cover. Animals everywhere. And because publishing is terribly progressive, and because Jen and I look out for it, a lot of those animals are girls. But still: a ton of boys. Because of the assumption.

Here’s an example: a truly great kids’ book is Lost and Found by Oliver Jeffers. I love this story, but on page 22, after being called “it” three times, an otherwise sexless penguin twice becomes “he.” This would never, ever happen the other way around. The only reason a penguin can abruptly become male in an acclaimed children’s book without anybody noticing is because we had already assumed it was.

Then you’ve got Smurf books. Not actual Smurfs. I mean stories where there are five major characters, and one is brave and one is smart and one is grumpy and one keeps rats for pets and one is a girl. Smurfs, right? Because there was Handy Smurf and Chef Smurf and Dopey Smurf and Painter Smurf and ninety-four other male Smurfs and Smurfette. Smurfette’s unique personality trait was femaleness. That was the thing she did better than anyone else. Be a girl.

Smurf books are not as common as they used to be, but Smurf stories are, oddly, everywhere on the screen. Pixar makes practically nothing else. I am so disappointed by this, because they make almost every kids’ film worth watching. WALL-E is good. I will grant them WALL-E, because Eve is so awesome. But otherwise: lots of Smurfs.

Male is default. That’s what you learn from a world of boy dogs and Smurf stories. My daughter has no problem with this. She reads these books the way they were intended: not about boys, exactly, but about people who happen to be boys. After years of such books, my daughter can happily identify with these characters.

And this is great. It’s the reason she will grow into a woman who can happily read a novel about men, or watch a movie in which men do all the most interesting things, without feeling like she can’t relate. She will process these stories as being primarily not about males but about human beings.

Except it’s not happening the other way. The five-year-old boy who lives up the street from me does not have a shelf groaning with stories about girl animals. Because you have to seek those books out, and as the parent of a boy, why would you? There are so many great books about boys to which he can relate directly. Smurf stories must make perfect sense to him: all the characters with this one weird personality trait to distinguish them, like being super brave or smart or frightened or a girl.

I have been told that this is a good thing for girls. “That makes girls more special,” said this person, who I wanted to punch in the face. That’s the problem. Being female should not be special. It should be normal. It is normal, in the real world. There are all kinds of girls. There are all kinds of women. You just wouldn’t think so, if you only paid attention to dogs and Smurfs.

Is it the positive role model thing? Because I don’t want only positive female role models. I want the spectrum. Angry girls, happy girls, mean girls. Lazy girls. Girls who lie and girls who hit people and do the wrong thing sometimes. I’m pretty sure my daughters can figure out for themselves which personality aspects they should emulate, if only they see the diversity.

It’s not like this is hard. Dogs and Smurfs: we’re not talking about searing journeys to the depths of the soul. An elephant whose primary story purpose is to steal some berries does not have to be male. Not every time. Characters can be girls just because they happen to be girls.

P.S. Don’t talk to me about Sassette. Sassette was like the three millionth Smurf invented. You get no credit for that.

Tomato parable

![]() I wrote some code to embed my tweets on my website.

There’s a statement that would have made no sense in 1990.

Actually, it barely makes sense now. But I did it. I’m proud

of my site. I built it myself. Occasionally

I get an email saying, “What software do you

use to run your site and how do I get it?” I think the answer is:

receive a Commodore 64 for your tenth birthday and no good

games.

I wrote some code to embed my tweets on my website.

There’s a statement that would have made no sense in 1990.

Actually, it barely makes sense now. But I did it. I’m proud

of my site. I built it myself. Occasionally

I get an email saying, “What software do you

use to run your site and how do I get it?” I think the answer is:

receive a Commodore 64 for your tenth birthday and no good

games.

But that’s not why I’m writing. I’m writing because I decided to grow my own vegetables. A few people I knew were growing their own vegetables, and they kept yakking about how wonderful it was, not depending on manufactured supermarket vegetables, which are evil for some reason, so I thought what the hell.

For a while I was intimidated by the idea of growing vegetables. When I reach for a vegetable, I usually just want to eat it. I don’t want to be intimately involved with its creation. I worried I would end up spending more time tending to the health of fragile, overly complicated peas than eating them.

Then I saw an ad for genetically modified seeds. These promised to take the hassle out of growing vegetables, which seemed pretty intriguing. The tomatoes would be big and red and I wouldn’t have to do anything. So I got those.

This upset my hippy friends. Especially when I started having problems. My frankenfruit was supposed to be simple but after a few weeks the whole garden stopped growing. My cabbages were flaccid. My carrots were anemic. My spinach wouldn’t self-seed. It wasn’t supposed to self-seed. The genetics company had engineered it not to, so I’d have to buy new seeds each season. But I thought there should be a way around that.

I asked my hippy friends for help. Well! You’d think I asked for a kidney. They kept bringing up the fact that I was using GM seeds. Eventually they all got together and said, “Max… we can’t help you any more. We want to. But you brought these problems on yourself. And the thing is, when you ask for help, you’re actually asking us to use our skills and knowledge to prop up a corporatized product that’s not just practically inferior to the free alternative you ignored, but actually bad for the world. We just can’t do that.”

And that was how I taught them to stop asking me for help with Windows.

10 comments

10 comments