Writing Blogs

Displaying blogs about Writing. View all blogs

Mind of the Agent

![]() I remember when I was desperate to find a girl but had no idea what

they wanted. I knew what I wanted. I wanted them to take delivery

of my package. But how to convince them? What did they want from me?

Where could I find one with a good reputation, who didn’t charge

fees?

I remember when I was desperate to find a girl but had no idea what

they wanted. I knew what I wanted. I wanted them to take delivery

of my package. But how to convince them? What did they want from me?

Where could I find one with a good reputation, who didn’t charge

fees?

Wait, did I say girl? I meant literary agent. I couldn’t find a literary agent.

Now there are tons of sites about literary agents. Some are by agents. My favorite is Nathan Bransford of Curtis Brown, but there are plenty to choose from. There’s no longer any excuse for not knowing at least a little about how an agent’s mind works: what they’re looking for, how to approach them.

Still, the other day I received an email from a writer facing a quandary:

A Literary Agent has given me a favourable reply (ie: wants to see my entire manuscript from a lousy query letter), so I immediately panicked and sent it to a “professional editing” service (one listed on Australian Literary Agents Website) for a final Mr Sheening. Do Literary Agents have a time limit before they get miffed if you don’t send manuscript by return email? The Editing Service assures me that I have two months (?) to submit, as they have not started it yet, but “it is on the top of their pile”.

Help… please?

Yours in awe

Elle

Usually I can’t respond to emails, but I make an exception for those that sign off, “Yours in awe.” So I replied, and then I thought I might as well post my response here, because it was just that good. Or possibly not, but what the hell, it’s not like I’m forcing you to keep reading.

Hi Elle!

This is why you don’t query agents until your book is ready, of course. But I know it happens. I queried a few agents with my first novel then freaked out because what if they wanted to see it? I think I did lightning rewrites every time someone responded.

I see two issues. The first is: Are you damaging your chances if you don’t respond to an agent immediately? If we were talking about American agents, I’d say, “Maybe.” Most reputable American agents receive more queries than they can remember, and might not notice whether it’s been two weeks or two months since they asked to see yours. But they might.

For an Australian agent I’d say, “Probably.” They deal with far fewer writers and are more likely to wonder what’s going on.

But either way, I’d send them that manuscript. Agents want reliable clients, and if the first thing you do is delay, they’ll worry you are one of those writers who are forever six months away from finishing their next book. For this reason you should not reply with some pathetic story about how you thought your book was ready but now you think about it can you please have a few more months. Don’t do that.

You are worried that your book could be better; well, it probably could. They all could. Do you think yours has little flaws or big ones? If they’re minor, they’re unlikely to dissuade an editor who otherwise loves your work, and if they’re major, you’re dead no matter what: dead if you send in that piece of crap, dead if you wait for two months only to discover from this editing service that you need to spend six more on rewrites.

Speaking of which. There are very fine freelance editors out there but I don’t like the concept. In particular I think it’s bad for amateur writers with no idea what’s good and bad about their book to consult a freelance editor in the hope that this expert can explain it. It’s bad because (a) to rewrite well you need to completely believe in what you’re doing. Receiving advice you don’t really understand or agree with but feel compelled to follow anyway because it’s coming from an expert will crush everything unique and valuable about your book.

And (b) some freelance editors are delusional psychopaths.

By my reckoning, about one in four pieces of literary feedback are so wide of the mark they’re not just unhelpful but destructive. They want your book to be more like a completely different type of book, or prostrate itself before the altar of Strunk & White, or not imply things about hot-button issues you never even thought of, or go into depth about things nobody cares about, or not do this mildly felonious thing that someone tore strips off them for at their last story workshop, or stop reminding them of their ex-wife.

I’m talking about feedback from other writers and readers, rather than editors; you would hope freelance editors are less delusional than writers. But I don’t know. Why take the risk? This is why I advocate quantity: get your ms. read by at least eight or ten people before you show it to anyone in the industry. Enough to identify the outliers.

Obviously I haven’t read your manuscript (that wasn’t an invitation). I don’t know which editing service you’ve selected, or how experienced you are, or whether you’ve workshopped it already. But based on what I know: send it. You’re more likely to hurt yourself by not sending it than you are to help yourself by delaying for months in order to maybe improve it but maybe not.

Good luck!

Max.

My Stupid Industry

![]() Lately the publishing industry has been trying to commit suicide over

electronic rights. It’s funny because every time in history a

revolutionary new way to do business comes along, the first instinct of

all established players is to strangle themselves

with it. Movie studios fought the VCR. Microsoft fought the Internet.

The music industry fought MP3s. TV networks are fighting PVRs.

Eventually, these turn into important markets, fully embraced by the

companies that tried to kill them. But until then everyone spends a lot

of time throwing lawyers at anything that doesn’t

look like a traditional business model.

Lately the publishing industry has been trying to commit suicide over

electronic rights. It’s funny because every time in history a

revolutionary new way to do business comes along, the first instinct of

all established players is to strangle themselves

with it. Movie studios fought the VCR. Microsoft fought the Internet.

The music industry fought MP3s. TV networks are fighting PVRs.

Eventually, these turn into important markets, fully embraced by the

companies that tried to kill them. But until then everyone spends a lot

of time throwing lawyers at anything that doesn’t

look like a traditional business model.

The first e-madness was DRM, of course. That’s the code they wrapped around electronic books to ensure they couldn’t be pirated. Well. “Ensure” is a big word. I’m not sure that any piece of DRM in history has survived an interested hacker. What it did ensure was a steady trickle of emails to my inbox from people who couldn’t find an electronic copy of Jennifer Government in the right format for their device, or could but after they paid their money it didn’t work.

Next came e-delays, where publishers held back electronic versions for four months following print publication. “The right place for the e-book is after the hardcover but before the paperback,” said Simon & Schuster CEO Carolyn Reidy. This is a brave counterpoint to the more common wisdom that the right place for selling something is wherever customers want to buy it. So we were not just restricting e-books to particular formats within particular territories, but also to particular windows of time.

But that wasn’t enough. Publishers didn’t like the fact that Amazon.com started selling e-books for $9.99 each. (They thought that was too cheap, if you’re wondering.) It didn’t affect publishers’ margins, nor authors’ royalties, since Amazon.com was selling below cost to promote its Kindle platform. But still, publishers were uncomfortable with the idea of books being that cheap. So they went to war and forced Amazon.com to bump up prices to $13-$15, in exchange for taking a lower royalty on each sale.

Let’s review. Amazon.com was eating it in order to allow you to buy books for ten bucks, instead of twenty or thirty, while paying authors the same royalty. Publisher intervenes, and now books are more expensive for you, while the author gets less. Also, the publisher gets less. Oh, and I didn’t mention this, but during the war, Amazon.com took down all the “Buy” buttons for Macmillan books, so you definitely couldn’t buy them no matter how much you wanted to and nobody made any money at all.

I won’t say it’s impossible for an industry to push retail prices up while pushing their own margins down and be successful. I’ll just say that’s not the way it usually works. Also, as a general rule, when customers want to buy a product, it usually works out best if the company lets them. I don’t think there have been too many examples of companies making money while refusing to sell their products in the formats their customers want while also forcing retailers to charge more and pocketing less themselves. I’m not sure. But that’s my feeling.

Meanwhile, rocked by the Global Calamitous Money Disappearing Event, publishers began cutting back what they do. Ten years ago, a publisher gave hopeful authors editorial advice, a printing service, a promotional budget, and access to bricks and mortar bookstores. There was really no viable alternative, short of becoming a small publisher yourself. To become a successful author, you needed a publisher.

Today, the promotional budget is more likely to involve encouragement to do something on the internet rather than a book tour. Publishers are still fantastic at getting you into bookstores, and physical books still comprise the vast majority of the market: you need them for this. But in e-books, you can click “Export to EPUB” as easily as they can, and without giving up 75% of revenue.

Also, publishers are getting less willing to make risky bets. Instead of taking an unknown author and striving to find her an audience, they want authors to establish their own audience in advance, via a website or similar.

Now, publishing is full of terrific, smart people who love books and want to promote authors. I haven’t met a single person in publishing I didn’t like. I even love my old Viking editor, who dumped me via relayed e-mail message. I forgive you, Carolyn. I really do. But the people in charge there are trying to sue the VCR. If publishing gets tomorrow everything it wants today, it will be smaller and less relevant. Imagine the world in in ten years, when e-books are 50% of the market: What will publishers offer authors? Not the ability to find an audience, if they’re pushing that onto authors. Not the distribution network: anyone can get their book into an electronic store. Not promotion; or at least, not much of it. That leaves editorial and distribution of hard copy. Not to be sneezed at, for sure. Editorial in particular is often the difference between a great book and a mediocre one; I can attest to that. But if I’ve got a web site and a hundred thousand visitors, I’d think seriously about whether editorial and print is worth giving up 90% of my income. I would, at the least, drive a harder bargain with a publisher than if they were providing more services I really needed.

The publishing industry is trying to think long-term, like every industry that faced a revolutionary change before it. But please, this time, can we not batter ourselves to death? It’s not that complicated, Publishing. I write stories. I want people to read them. I want as many people to read them in whatever format they want, wherever they want, as cheaply as possible, while I earn a living. I don’t want lower royalties in exchange for higher retail prices. That’s the opposite of what I want. I don’t want to get emails from people saying they wanted to buy my e-book but they couldn’t because it wasn’t available or didn’t work. This is text. It’s not hard to put text on an electronic device. It’s only hard because you make it.

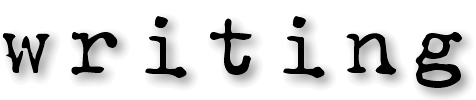

Fiction For Short Attention Oh Look At That Laughing Dog

![]()

Since

I got a iPhone, my bedside table has turned into a tower of books. It was

always pretty bad. But now it’s worse. Look at that. It’s a fire hazard. One

day I’ll toss a cigarette in there and it’ll be a conflagration. Not that I

smoke. That’s the only thing saving my life.

Since

I got a iPhone, my bedside table has turned into a tower of books. It was

always pretty bad. But now it’s worse. Look at that. It’s a fire hazard. One

day I’ll toss a cigarette in there and it’ll be a conflagration. Not that I

smoke. That’s the only thing saving my life.

The problem is when I go to bed, instead of picking up a book, I think, “I’ll just check Reddit.” Or Twitter. Or the news. Or Facebook. Or my email. Not or. And. I check all those things. I have 65 apps. I just counted. Halfway, I thought, “I wonder if there’s an app for counting your apps.” I was tempted to take 20 minutes and hunt one down, so I wouldn’t have to waste ten seconds the next time I need this information. You see what’s going on here. It’s a sickness.

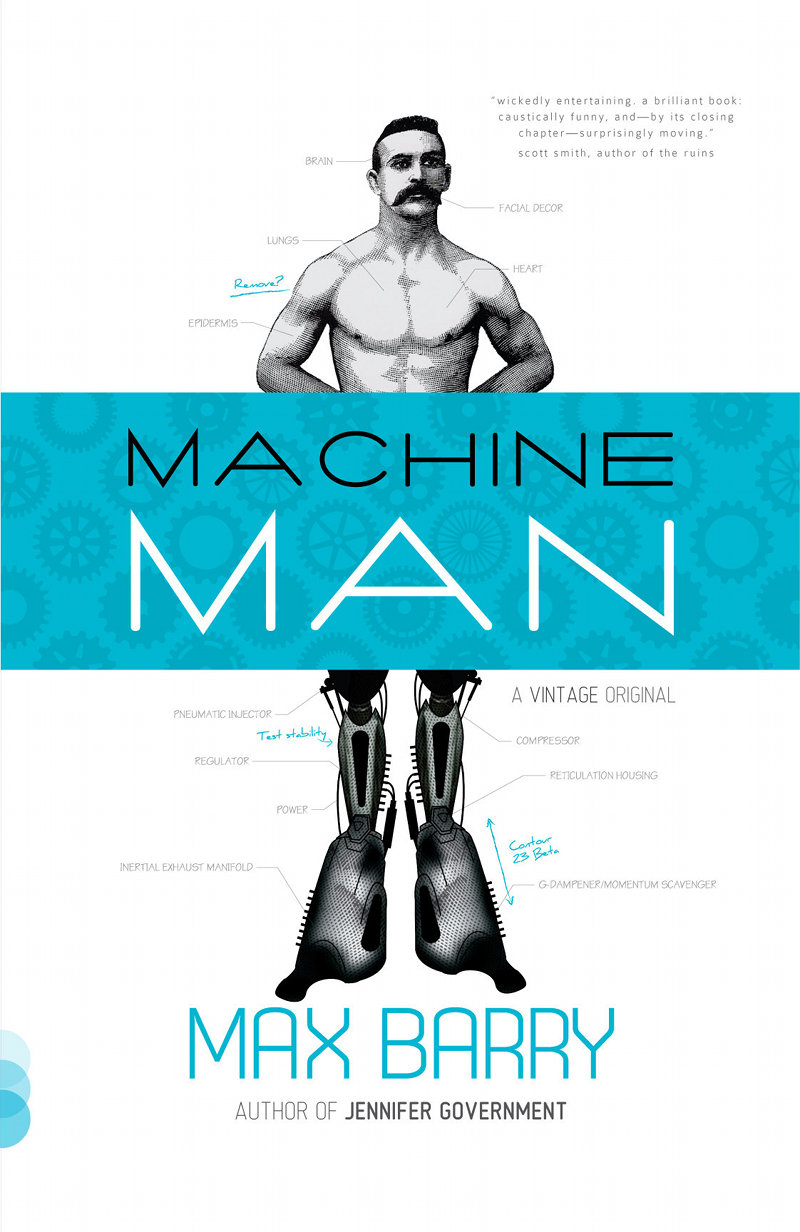

It’s got me thinking I should do more short attention span fiction. Maybe another serial, like Machine Man. Firstly, because that was fun as hell, in a terrifying kind of way. Secondly, because I’m rewriting it as a novel, and it’s pretty great. I already have the story. Now I get to play around in all the spaces I skipped over because the serial had to go go go. It’s a good system.

But thirdly because maybe no-one has the time to sit down with entire novels any more. Or rather, maybe there is a class of people, to which I belong, that is becoming addicted to bite-sized information delivered by scattershot. I hope there’s a class. I hope it’s not just me.

Not that it has to be one or the other. I’m not saying that once you sign up to Facebook, you abandon Margaret Atwood. Although I have done exactly that. The Year of the Flood is just sitting there. What I mean is that the novel seems to be getting more competition. The novel is very strong, of course; there is no replacing the novel. But the competition is pretty great. The internet is everything in bite-sized pieces. It’s candy-flavored stream of consciousness of whatever you want.

And increasingly the same device will access both. I’m having trouble getting to novels just because an iPhone is in the same vicinity. What happens when my books are actually on my phone? Or in my iPad? When I’m one swipe away from the web, will I still be able to completely sink into a novel? Plenty of times I’ve slogged my way through a book that wasn’t really holding my attention just because it was there, in my hands. I don’t think I’d do that on an iPad. I think I’d tap that bastard into oblivion and answer an email.

So I am interested in fiction that works with the internet, rather than fights it. Something that doesn’t sit there, 400 pages heavy, asking for a seven-hour commitment before I start. That’s the kind of fiction I’d like to read right now. Something that sneaks under my guard and pries me away from memes and status updates. I would like to find that.

It’s Not Me, It’s You

I’ve written more bad fiction than you’ve read. I’m serious. I’ve done a hundred or so drafts of nine or ten manuscripts, and let’s not even start on the shorter stuff. Read one of my books? Think it could have been better? Well that’s what they published. That was polished.

After a decade of wrangling paragraphs for a living, I have decided: it’s always the book’s fault. When your scene won’t quite come together, your novel idea won’t stay interesting, your main character refuses to fill out: it’s not because you lack talent. It’s because your idea is stupid. You’re trying to push shit uphill. And you may be a good shit-pusher, with a range of clever and effective shit-pushing techniques, but still: it’s going to be hard, frustrating, and ultimately you’ll discover you still don’t have your shit together.

I used to believe that an author needed an iron will. Discipline, to forge through the bitter dark and emerge clutching a tattered, tear-stained first draft. Now I think that’s a good way to lose nine months on a bad idea. Because if you have any skill as a word-slinger, you can make a bad idea sound okay. Not brilliant. But mildly interesting, at least for a while. Keep pushing that shit, though, and depression sets in. That’s when you think: I’m not good enough. Or: If I were more disciplined I’d finish this. Or: I can’t write.

Sure you can. You just can’t write this and stay interested, because it’s a stupid idea. It’s predictable. It’s been done. It had one intriguing aspect and you tapped that out within the first three pages. You don’t want to write this because your body is bone-bored of it.

A good idea excites you. It makes each day of writing a little joy. A good idea, when you peel it, has more good ideas inside. It makes you feel clever. It doesn’t need to be articulated. It might sound silly when you try to explain it. (Don’t try to explain it.) But you know there’s something there. It pulls you to the keyboard. It spills words from your fingertips. Some days, you lose your grip; you wander from the path and lose sight of where you were. But a good idea calls out to you.

A while ago I had The Block. The way I got out of it was to write a page of something new every day. The first week, I flushed out a lot of ideas that had been humming around the back of my brain, promising me they were brilliant. They weren’t. I captured them one page at a time and set them aside. The second week I wrote two things that were kind of interesting. Not very interesting. But not abominations, either. It was possible to imagine that in some alternate universe of very low standards, they could become novels. Not popular novels. But still.

The third week, I wrote something interesting. And I discovered I could write. That the reason I’d been stuck wasn’t because I’d forgotten where the keys were. It was because the story I was trying to make work sucked.

So that’s my advice to anyone mired in a story. Don’t blame yourself. You’re great. It’s just that stupid idea.

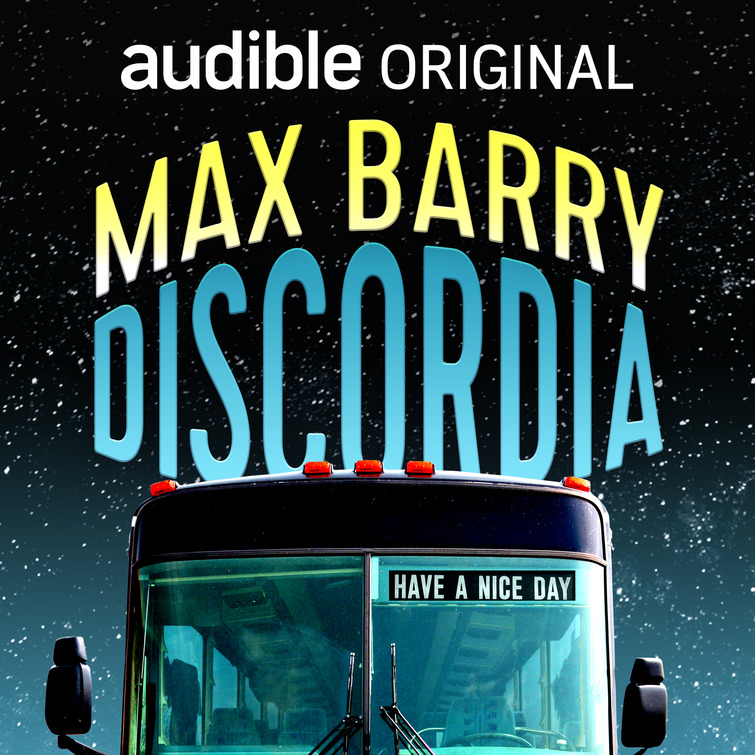

A Business Fable

![]() Once upon a time a boy went to business school. The boy was not sure he wanted to go into business, because what he most loved was writing stories about aliens and monsters and girls who did not love him back. But he knew he could not hope to earn a living from such stories, so business school it was.

Once upon a time a boy went to business school. The boy was not sure he wanted to go into business, because what he most loved was writing stories about aliens and monsters and girls who did not love him back. But he knew he could not hope to earn a living from such stories, so business school it was.

The boy learned many interesting things, until he began to think perhaps business was for him after all. One day, he attended a class in which students were divided into groups and asked by the lecturer to solve the following puzzle:

“A man buys a horse for $400. He feeds it, trains it, and sells it to a racetrack manager for $500. However, soon he regrets his decision, and asks the racetrack manager if he can have the horse back. The racetrack manager, being a good capitalist, asks for $700. The man objects, seeing no reason why the horse should be worth so much more than the day before, but eventually he relents and accepts the loss. Some years later, he finally sells the horse to neighbor for $800. Question: What is his total profit or loss?”

The boy’s group began to discuss this puzzle. The boy thought the solution was fairly obvious: the man bought and sold the horse twice, making $100 profit each time. However, his teammates were seduced by the puzzle’s suggestion of a loss, and insisted this be accounted for. They thought the man broke even.

The boy tried to explain his reasoning a different way. He added up the man’s outlays and revenues, showing the difference was $200. The group agreed, but insisted this was then canceled out by the loss. The boy tried again. “Imagine it’s not the same horse,” he said. “The man buys and sells one horse, then buys and sells a second horse.” The debate became heated. There was no second horse, the group insisted. There was one horse, and the man broke even.

After a few minutes, the lecturer halted the exercise and asked each group for its verdict. Only unanimous decisions would be accepted. Every other group in the class declared their belief that the man broke even. The boy’s group hissed at him to bow to the majority opinion, but he could not bring himself to do it. They informed the lecturer that they could not agree.

The answer, said the lecturer, was that the man made $200 profit. However, the exercise was not about that. It was designed to test teamwork. He had observed most groups working effectively: establishing leadership roles, managing divergent opinion, and finding common ground to reach a shared solution. The boy’s team, however, was a textbook example of failure: it had allowed a disruptive element to block them from consensus. It was then that the boy decided business was probably not for him.

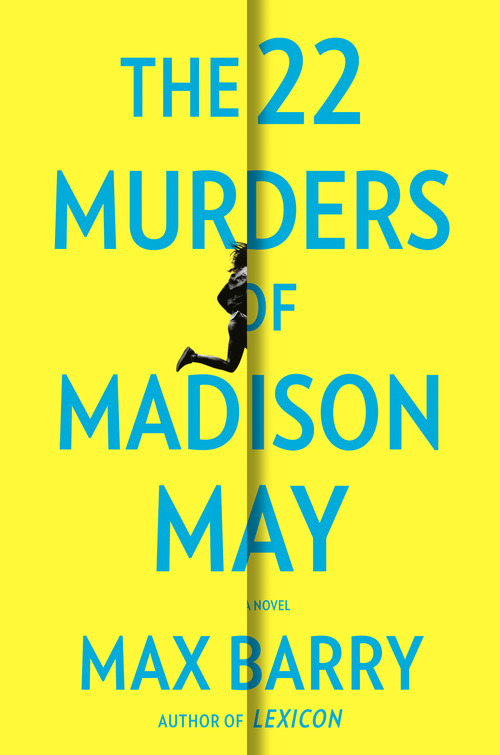

A Short Story Broke My Brain

![]()

You

might be wondering what happened to

that live short story. I did it.

I just haven’t written about it because I lost the ability to form coherent sentences.

You

might be wondering what happened to

that live short story. I did it.

I just haven’t written about it because I lost the ability to form coherent sentences.

I knew it would be tough. Turning up at the Melbourne Writers Festival with a laptop, plugging into the big screen, and writing a short story from scratch while people watch: that’s not the recommended writing technique. I think that’s the opposite of what you’re supposed to do, which is something about forgetting the rest of the world exists. It’s hard to be creative and self-conscious.

But that was half the fun! Come watch Max struggle! I was already writing an online serial in real-time; how much worse could this be?

Lots. I turned up on the day, ready for action, at the table they’d set up. It was in the corner of the atrium, hidden behind the Festival’s Information Desk. On official maps, you couldn’t see it, because it was obscured by the word “INFORMATION.” This struck me as problematic. There was no signage to indicate who I was or what I was doing. Shortly after I began to set up, a man stopped and asked for directions to a panel. I decided it was time to make up my own signs. I did three, and stuck them to the front of the table: the first said, “Hi! I’m Max Barry.” The second said, “I’m writing a live short story today.” The third said, “Because I’m stupid, that’s why.” This turned out to be truer than I knew.

Half a dozen people had gathered. About this number stayed the entire three hours, and may I say to those people, I’m incredibly touched and grateful, even though you destroyed my sanity. There was nowhere for them to comfortably see the screen and me at the same time, but that didn’t deter them; oh no. They made the best of things, craning their necks and reclining chairs like they were beach lounges. That way, they could see pixelated, perspective-warped words on the big screen while staying close enough to make out the individual beads of sweat dripping down my nose.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. First I had to chase down Festival people, imploring somebody to plug me into the big screen like we had damn well arranged. I hate to knock the Festival, because it’s a great event, but this was really crap. People were waiting.

Once I was on the air, I canvassed my little audience for ideas. I got some great ones, some good ones, and some I still don’t understand today. The two that jumped out at me were both about pregnancy: one about a couple whose due date comes and goes, and goes and goes, and another about renting a baby. In retrospect, I probably should have been wary of both of these, because they’re similar to two other shorts I’ve written: How I Met My Daughter and A Shade Less Perfect. I was already defensive, feeling around for tried and tested tools.

But it was only 11:30am: I was full of energy, optimistic! When people came up and asked for directions, I tried to help them out, then went back to my notes. Sometimes I asked for feedback from the people standing around. Then I realized I didn’t have to: I could hear their reactions.

Let me say that again. I would type a sentence, and hear people inhale, or snicker, or lean together to discuss it. Now, I guess I knew this might happen. And, at first, while I was messing around with notes, it was funny. Even useful. But then I started writing. And it was like they were INSIDE MY BRAIN.

The longest I ever sunk into the story before remembering that people were watching was about 45 seconds. Often I would be halfway through a sentence and someone would stop by to chat or offer suggestions or ask where the bathrooms were. Which is what I signed up for, of course: this was meant to be interactive. But it was like being woken from a deep sleep eighty times an hour. Two parts of my brain that don’t normally meet were knocking into each other and I wasn’t sure which of them was me.

By the two-hour mark, I was flagging. The story wasn’t awful, but it didn’t feel right. It was derivative, of me; like something not new. I wasn’t connected to it. I had honestly tried to do this right, but if I’d been at home, at this point I would have closed the document and checked my email.

Since that would have been inappropriate with an audience, I ploughed on. At 2pm, I finished. I thanked everyone who had stuck around, and I meant it, even though I already knew I would be spending the next few days trying to scrub them out of my brain. Then I left. I felt like someone had beaten the creative part of my mind with sticks. The rest of the day, I struggled to talk like a human being. True, I have that problem normally. But this was even worse than usual.

The next time I sat down in my study, I felt them there: phantom story-watchers. Halfway through my first sentence, I almost braced for a snicker. But it didn’t come. After a while, I forgot about it. I was okay. I was safe again.

10 comments

10 comments