They Want You

![]()

Here’s

something to try: spend the next day actually noticing every

ad that features a photo of someone looking at you. Magazine

ads, bus station posters, billboards: all these. Now think about

what kind of situation you’d have to be in for this person to

be looking at you like that in real life.

Here’s

something to try: spend the next day actually noticing every

ad that features a photo of someone looking at you. Magazine

ads, bus station posters, billboards: all these. Now think about

what kind of situation you’d have to be in for this person to

be looking at you like that in real life.

If where you live is anything like where I live, you’ll find that for a very high number of these, the situation would have to be one of:

- They want to have sex with you

- You just told them the funniest joke in the world ever

- You just told them the funniest joke in the world ever and now they want to have sex with you

This is an entertaining exercise not just because it’s amusing to think about Kate Moss wanting your body, but also because it reminds you how far the arms race between advertising agencies and your brain’s perceptual filters has advanced. The more ads there are, and the more they try to get our attention, the better we get at not noticing them, so marketers have to continually up the ante. Apparently we’re now in a state where most ads are full of people looking at us in a way that would heat us up down to our toes if it happened in real life, and we don’t think anything of it.

Caring about Copyright

![]() I was pretty sure that nobody gave a stuff about copyright, but my

last blog

got quite a big response, so either lots of people care about it,

or only a few do, but they all have internet access. There was much

challenging of my argument that copyright should last just ten

years, so, in the time-honored tradition of half-assed essayists

everywhere, I have decided to Q&A myself.

I was pretty sure that nobody gave a stuff about copyright, but my

last blog

got quite a big response, so either lots of people care about it,

or only a few do, but they all have internet access. There was much

challenging of my argument that copyright should last just ten

years, so, in the time-honored tradition of half-assed essayists

everywhere, I have decided to Q&A myself.

(And this is totally irrelevant, but I notice it’s always more fun to write the questions than the answers. It must be the same way evil characters are more enjoyable to write.)

“Since you think a 10-year copyright is such a good idea, obviously in four years’ time you won’t mind if I sell my own print run of Syrup.”

If you publish a reprint of Syrup in 2009, you won’t be infringing my rights: you’ll be infringing Penguin Putnam’s. That’s what happens when you sign with a publisher: you grant it the exclusive right to sell copies. I no longer have the ability to put my novels into the public domain.

“Very convenient. When you sell your next book, then, will you insist that your contract lasts only ten years, after which your books enter the public domain?”

What am I, crazy? If I did that, my publisher would become confused and frightened, I would get a lot of e-mails about “the way we always do things”, and when it was all over I would probably be looking at either a much smaller advance or none at all.

“Aha! Sir, you have been exposed! You say it would be a good thing for copyright to be ten years, yet when given the option, you won’t do it yourself!”

Exactly. My argument is not that shorter copyright would be good for artists. I’m pretty sure it would be bad: not terrible, but definitely worse, at least for people like me who create (arguably) wholly original content. My argument is that it would be good for society, and that’s more important than what’s good for authors.

“Why, you greedy, self-centered hypocrite. You admit that you refuse to do what’s best for society, then?”

Yes. I mean, sure, I’m nice: I recycle my glass and paper, I give to charity, and I smile at my neighbors. But I’m not going to work for free, or take a pay cut, just because I think society deserves to have more of my work for less. It would be good for society for garbage-collectors to take a pay cut, too, but I don’t think they toss and turn at nights about the ethics of it.

When it comes to my career, I plan on doing what I think will help it best. There is a reasonable argument that releasing your work for free helps your career, and I partly agree with this, which is why my short stuff is available for anyone to copy, print, and even sell. But I’m not quite at the Cory Doctorow level, which involves putting your entire novel up for free download. If I thought it would be good for me, I’d do it. But I don’t, and there’s no ethical reason why I should. That’s why we need a change in the law: without it, artists and companies will act in their own best interest, and generally that means grabbing as many rights as possible and hanging onto them forever.

Incidentally, on a systemic level I think there’s something seriously wrong with any plan that requires a lot of people to act against their self-interest. It never works, and the people who benefit most are usually those who don’t join in. The monster that copyright has become can’t be killed by a handful of authors valiantly giving up some of their income, and nor should it be. The law has to be changed. Then everyone can be left to pursue life, liberty, happiness, and profit in the usual, capitalist way.

“Max, you fool. If there was a ten-year copyright, film studios would never buy another book. They’d just wait until the copyright expired and make their film while the author slept in gutters and juggled kittens while begging for food.”

Studios can already make film versions of old books without paying the author a cent, and they’re still buying copyrighted books. There are two reasons, I think. First, if a book-based movie gets made for $25 million, the author pocketed maybe $500,000. A 2% saving is not enough to get a studio worked up.

Second, public domain properties are less valuable, because there are no exclusive rights: the studio can’t do merchandising tie-ins, or make a spin-off TV series, or sequels… or, at least, they can’t do so exclusively. The monopoly is what makes rights valuable, and that’s true whether it lasts for ten years, or twenty, or a hundred. There will still be a massive financial advantage in being the only publisher allowed to produce the new Harry Potter book, and the only studio allowed to make the film, even if that right expires in a decade.

“But the idea of a some sleazy publisher cranking out copies while the author gets nothing… it disturbs me.”

Well, the author gets exposure, which is valuable if he’s unknown, because it builds an audience that might buy his newer books. (In fact, if the author is unknown ten years after his first book, he may be the sleazy publisher: he may re-publish his own work.) If, on the other hand, he’s already well-known… well, he probably isn’t starving.

But to me this is largely irrelevant. I know a lot of people believe in the moral right of an artist to control his or her work, but I don’t. If you invent the telephone, you get a twenty-year monopoly; I don’t see what’s so extra-special about Mickey Mouse that deserves an additional century. Besides, if we’re designing a system to encourage the production of creative works, how happy or rich particular individuals within that system get is of no consequence: what’s important is how well the system works.

“I’ve spent ten years trying to flog my novel to publishers. Under your half-baked scheme, it would have no copyright left!”

I’m pretty sure that the copyright clock starts ticking on the first publication of a work, not on the date of its creation. Also, if you substantially revise a work, you get all-new copyright.

Okay, that’s enough on copyright, I promise. We return to the real world next blog.

Writers for Less Money

![]() Last night I was re-reading that Bible of

Hollywood screenwriting, William Goldman’s

Adventures in the Screen Trade,

when I came across this:

Last night I was re-reading that Bible of

Hollywood screenwriting, William Goldman’s

Adventures in the Screen Trade,

when I came across this:

(This) was, ultimately, responsible for the existence of Hollywood. All the major studios paid a fee to Thomas Edison for the right to make movies: The motion picture was his invention and he had to be reimbursed for each and every film.

But there was such a need for material that pirate companies, which did not pay the fee, sprang up. The major studios hired detectives to stop this practice, driving many of the pirates as far from the New York area as possible. Sure, Hollywood had all that great shooting weather. But more than that, being three thousand miles west made it easier to steal.

This morning, I saw this article on how the British government is planning to extend copyright protection from 50 to 100 years. This would bring it more or less in line with the US, which grants copyright until 70 - 95 years after the author’s death—a period extended in 1998 after lobbying from media companies, primarily Disney.

I’m a writer and earn my entire living from copyright, but this is nuts. Copyright has become a corrupt, bastardized version of itself. Rather than serving as a way to encourage creative works, today it’s a method of fencing off ideas and blocking creativity. And some of the companies pushing hardest for new intellectual property laws are the same ones that owe their existence to breaking them.

We invented copyright to encourage innovation: to make it worthwhile for people to create their own artistic works, rather than copy and sell someone else’s. The aim is not to bequeath eternal rights to an idea, or to make artists fabulously wealthy; it’s to provide society with new books, films, songs, and other art. Copyright provides incentive, but the incentive itself is not the point of the law: the point is to encourage creative behavior.

Having a few years of copyright protection is a good incentive. But a hundred years? Or seventy years after my death? (If I live to 80, it will become legal to print your own copy of Jennifer Government in 2123.) There’s no additional incentive in that. There is nobody, and no company, thinking, “Well, this is a good song, but if I only get to keep all the money it makes for the next 50 years… nah, not worth developing it.”

Copyright extensions, of the kind popping up everywhere lately, have nothing to do with encouraging more creative work, and everything to do with protecting the revenue streams of media companies that, a few generations ago, had an executive smart enough to sniff out a popular hit. It’s a grab for cash at the public’s expense. The fact that there is any posthumous copyright protection at all proves that the law is intended to benefit people who are not the original creator: that is, heirs and corporations. The fact that copyright extensions retroactively apply to already-created works proves they’re not meant to encourage innovation. The only reason copyright extension laws keep getting passed is because the people and companies that became fabulously rich through someone else’s idea are using that wealth to lobby government for more of it.

I’d make copyright a flat ten years. You come up with a novel, a song, a movie, whatever: you have ten years to make a buck out of it. After that, anyone can make copies, or create spin-offs, or produce the movie version, or whatever. Now that would be an incentive. You’d see all kinds of new art, both during the copyright period, as artists rush to make the most of their creation, and after, when everybody else can build on what they’ve done and make something new. You’d see much cheaper versions of books and movies that were a decade old. You wouldn’t have the descendants of some writer refusing to allow new media featuring the Daleks, or Tintin, or whatever. And artists with massive hits would be merely rich, not super-rich.

A century-long copyright (in the UK), or a lifetime plus seventy years (in the US) means books, songs, and films created before you were born will still be locked up when you die. During your life, you will see no new versions, no reworkings, reinterpretations, remixes, or indeed any copies at all, unless they are approved by whoever happened to inherit the original artist’s estate, or whichever company bought it.

Media companies are quick to throw around the word “thief” whenever a teenager burns a CD or shares a file over the internet. But this is theft, too, when an artist’s work is kept away from the public for a century. Ten years is incentive. A hundred years is gluttony.

Get your brave new world right here

![]() Occasionally I wonder how social values will change over the next

several decades. I’m pretty sure they will change, and our

descendants will look back on the early years of the 21st century and find

some of our ideals bizarre—as repugnant as we find slavery, sexism, and

repression. But which ones? Here are some guesses.

Occasionally I wonder how social values will change over the next

several decades. I’m pretty sure they will change, and our

descendants will look back on the early years of the 21st century and find

some of our ideals bizarre—as repugnant as we find slavery, sexism, and

repression. But which ones? Here are some guesses.

-

Speciesism.

As a race, we’ve shown a pretty clear trend toward abolishing arbitrary divisions

between people. We no longer consider some races to be sub-human, for example, or one

gender to be undeserving of the vote.

Ethical vegetarianism, practically unheard of a century ago, is increasingly common,

and animal cruelty is now widely considered to be a terrible thing.

To me this suggests we’re on the way to overthrowing

the belief that animals have no feelings worth considering, and that we have the

right to eat them. I don’t think we’ll ever consider animals to be our equals, but we

won’t think their feelings are worthless, either.

Prediction: First we’ll outlaw agricultural practices that cause animals pain, and eventually we’ll stop eating them.

-

Patriotism.

When you’re under threat, patriotism makes a lot of sense:

your chances of survival go up if you band together with similar people.

But as globalization brings people of all nations closer together,

making international travel and communication astonishingly easy,

national boundaries mean less. The more we learn about foreigners,

the more we find we have in common with them; and not only that,

as the world undergoes a slow, inevitable cultural homogenization,

we do have more in common with them.

At the same time, a consistent pattern shows up every time citizens of a large Western nation go to the ballot box: city-dwellers vote liberal and country people vote conservative. How long before residents from Manhattan, London, Sydney, Paris, and Berlin have more in common with each other than they do with rural residents of their own country? Do they already?

Patriotism is a pretty crappy ideal in the first place. It’s clearly untrue that people who happen to have been born in your country are more special or worthy of your support than people who happen to have been born somewhere else. In fact, patriotism is even less defensible than racism, because at least there you have a biological basis on which to discriminate. When you’re patriotic, you’re using an imaginary line.

Prediction: Eventually people won’t identify themselves primarily by their nationality, but rather by their belief system.

-

Faith.

Recent events in certain Western countries notwithstanding, the influence of

religion on people’s lives has been falling for as long as recorded human

history. So I don’t see why it should stop now.

Prediction: Few people will believe in a literal God or identify themselves as followers of a religion.

-

Privacy.

There’s more concern about privacy in democratic countries today, but there is less actual

privacy. It’s increasingly difficult to interact with government departments and

corporations without supplying personal details, and, thanks to improving technology,

it’s increasingly easy for those bodies to amass, analyze, and use that

information. Governments have strong incentives to invade people’s privacy, since

it increases their ability to control the populace, and they have very little

incentive to protect privacy.

As technology creates more powerful and more easily accessible weapons, a single rogue person will be capable of inflicting greater harm on other people. The best defense against this is probably surveillance. Since human beings are more interested in safety than privacy, I don’t think we’ll fight hard enough against loss of privacy to stop it happening.

Prediction: People will no longer believe in a basic entitlement to privacy from government.

-

Selflessness. Regulated capitalism harnesses the power of

self-interest to make societies more productive. It generates enormous amounts of

wealth that, more or less, benefits society as a whole. Thus, capitalism is here to

stay for the foreseeable future.

However, capitalism rewards selfishness. People who act only in their own best interests tend to accumulate more money than those who don’t. For evidence of this, you don’t need to look any further than the types of personalities who end up running major corporations—or corporations themselves, which are by definition the purest embodiment of selfishness, and society’s biggest wealth-generators.

In capitalist societies, money means success: power, influence, and status. And since the wealthy are society’s winners, they are its role models. To succeed, others will emulate their behavior.

Prediction: People will believe less strongly in the moral duty to help others, and more strongly in the morality of self-interest.

That’s my best guess (for now): a society that looks back on mass-farming with horror, shakes it head at our obsession with flags, pledges, and anthems, sees little difference between religion and superstition, finds bemusement in our worries about privacy, and sees altruism as naive, even childish. Utopia? Well, not exactly. But then, I’m not predicting what I’d like to happen.

Dirt is Good. Dirt is Good. Dirt is Good.

![]() Today is an important day of celebration in Australia; it’s

National Dirt is Good Day.

No, really, it is. Now, I know, if you live in New Zealand, you’re wrinkling

your forehead and going, “Wait a minute, Max, Dirt is Good Day was

a few weeks ago,”

and if you’re Turkish or Pakistani it was

last year,

but that’s not important; those are just funny little international

differences, like how it’s currently Autumn in the Southern Hemisphere

and New Zealanders celebrate Christmas on the last Tuesday of February.

Today is an important day of celebration in Australia; it’s

National Dirt is Good Day.

No, really, it is. Now, I know, if you live in New Zealand, you’re wrinkling

your forehead and going, “Wait a minute, Max, Dirt is Good Day was

a few weeks ago,”

and if you’re Turkish or Pakistani it was

last year,

but that’s not important; those are just funny little international

differences, like how it’s currently Autumn in the Southern Hemisphere

and New Zealanders celebrate Christmas on the last Tuesday of February.

National Dirt is Good Day is sponsored by OMO, a washing detergent made by Unilever, and by “sponsored” I mean “invented.” Apparently you don’t have to be a government to go around inventing national days of celebration; anybody can do it. So Unilever has decided we need one in celebration of dirt. Here’s why:

Years of scientific study by child health experts shows that playing outdoors is an essential part of a child’s learning and development.

Getting dirty through constructive play is how children learn and express their creativity. It also helps them to stay healthy by encouraging them to exercise and bolstering their immune systems.

I dunno, it seems like this makes just as much sense without the phrase “Getting dirty through”. It seems like they inserted that fairly arbitrarily. But no, no, I’m not one to argue with unsourced “years of scientific study.” I should just be grateful that private enterprise has stepped in to deliver this crucial health message.

I clicked through the web site to find out how I could celebrate Dirt is Good Day at home—I don’t have any kids, but since it’s such a significant occasion, maybe I could pinch somebody else’s. The first couple of recommended activities seem interesting enough, but the further you go down the list, the more they seem to be basically, “Take one child, roll him around in the mud, and wash his clothes with OMO.”

The second-last one is “Mud Splatters”: its ingredients are (a) water balloons (b) mud and (c) paper. You’re meant to insert (b) into (a) and throw it at (c), marveling at “the amazing effects on the paper as the mud splatters.” There is no mention of the possibility of kids turning their attention to the amazing effects of mud splattering on other objects, including each other. Which seems like the logical progression to me, but apparently to Unilever it would be a surprising and unexpected development.

The final recommended activity is “Mud Pie.” The description is quite detailed, but I’ll summarize it for you: get a big pile of mud and try to make your parents eat it.

At the very bottom of that web page, in black text on a blue background, I noticed this:

Safety Note: Ensure children do not play with dirt that may have been contaminated by animals. Ensure that children do not put dirt or dirty hands in their mouths. Potting mix is dangerous as it contains a potentially harmful bacteria, do not use. Ensure any cuts are covered. Wash hands afterwards.

Wow! I always get a warm, fuzzy feeling when corporations take an interest in my personal wellbeing, but tucking away a safety warning where nobody will see it as part of a campaign to make children play in dirt is extra special. Maybe they should call it National Dirt is Good So Long as It Isn’t Contaminated by Animals and You Don’t Put it in Your Mouth and Wash Afterwards and Cover any Cuts and For God’s Sake Don’t Go Near the Potting Mix Day.

But it’s been a big success for Unilever, with consumers apparently embracing the message of: “No Stains. No Learning.” (An earlier draft, I’m guessing, is, “No Stains? Bad parent! Bad!”) So surely it’s just a matter of time before other companies jump on the bandwagon. There could be ExxonMobil National Go For a Long, Aimless Drive Day, or AT&T National Just Check Your Relatives Are Still Okay Day. Because they care about us, you know?

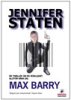

On Capitalism and Corporatism

![]() I am occasionally accused of being anti-things: anti-capitalist, anti-corporate,

and anti-globalization, mainly. If you’ve read Jennifer Government,

you may have an inkling why. But that’s a novel, not an essay. So I am

going to settle the burning issue: What Max is Anti-.

I am occasionally accused of being anti-things: anti-capitalist, anti-corporate,

and anti-globalization, mainly. If you’ve read Jennifer Government,

you may have an inkling why. But that’s a novel, not an essay. So I am

going to settle the burning issue: What Max is Anti-.

Let’s start with anti-corporate. People say this just because I wrote a book in which Nike commits mass murder as a promotion for sneakers. The truth is, I consider myself fairly pro-corporation. After all, I believe they should be allowed to exist. I’m happy for them to manufacture things, and offer those things to me in exchange for money. So long as they don’t externalize the true costs of such manufacture—by, for example, dumping their waste in a river—that’s totally fine. My only beef with corporations is that they would clearly kill any one of us if there was a clean profit in it, and they seem to be getting themselves into a position to do just that.

Now apparently that makes me anti-corporate. Which I think is totally unfair; after all, I can be pro-lawnmower even though I don’t want them running over my feet. I don’t believe that corporations are evil. I don’t think they’re immoral. They’re simply amoral: they have no capacity for ethical judgment. Like a lawnmower, they do what they’ve been designed for.

My attitude toward corporations doesn’t depend on whether they’re large or small, chain or independent, foreign or local. It’s certainly true that companies that serve the general public (like McDonald’s and Apple) act nicer than companies that don’t (like Monsanto and Halliburton), but this is no anomaly: it’s just further proof that corporations are only interested in public opinion when it affects their bottom-line. Fundamentally, all public companies are cast from the same mold. They are all machines, running different programs on the same operating system.

This is not a particularly common view in these days when corporations appear to us as grinning clowns and energetic bunnies. We are generally encouraged to view them as real people, complete with emotions and personalities and quirky senses of humor. To me this is the purest horseshit, and why I am never surprised by scandals of companies caught behaving badly. They are not people, and it isn’t cynicism to say so: it’s the plain truth.

(By the way, I suspect that the increasing personification of corporations might turn out to be their Achilles’ heel. The more society buys into the myth that companies are real people, the more we expect them to adhere to human-like standards of ethical behavior. People like me would allow corporations to get away with murder, because we expect nothing better. It’s the people who get shocked when they discover that designer-label clothing is manufactured for ten cents an hour by children in China who cause trouble for a brand’s image and force companies to improve their behavior.)

As for capitalism, I’m definitely pro- that. At least, I’m in favor of the kind of regulated capitalism that clearly beats the pants off any other economic system the world has come up with so far. Capitalism has its pointy bits, but it’s hard to argue with life-saving medicines, mobile phones, and being able to buy a vintage Chewbacca figurine over the internet. Now, I don’t think it’s a smart idea to privatize water, or the government, or any other essential service that isn’t subject to natural competition, but that doesn’t mean I’m anti-capitalist. That means I’m not a zealot.

Somehow, the words “corporation” and “capitalism” have gotten mixed up: the prevailing view is that corporations are champions of capitalism, while anybody prone to waving a placard outside a Gap store must be against it (and maybe even against *cough* *cough* freedom.) I don’t know how anyone who’s actually worked for a corporation can believe this. Companies are like the Soviet Union pre-1989: they’re centrally-managed, they’re always trying to establish a monopoly, and there’s nothing they love more than a little price-fixing. Sometimes they send people to lobby government, but not for more competition: no, they want subsidies, special favors, tax breaks, and government assistance. So who’s the pinko? It’s corporations that are anti-capitalist, not people like me.

Finally, globalization: I’m pro- that, too. Its great potential benefit is that as it erodes national boundaries, the privileges of rich nations leak out to the poor. Today, the single greatest determinant of your health, wealth, and general standard of living is which part of the Earth you happened to be born in—something you had no say in, and can take no credit for. There is currently some consternation in Western nations about jobs flowing offshore, to people who will work for less pay (although this has been the case ever since I can remember, just in different industries), but as far as I’m concerned, this is terrific. As much as it would suck to be made redundant from your call center because the work is moving to India, that job is going to someone poorer than you, who needs the work more than you, and who in unemployment faces more serious consequences than having to cancel his World of Warcraft subscription. We are gradually coming to grips with the concept that people shouldn’t be discriminated against for things they can’t control, and thanks to globalization, this will eventually apply to people outside our own national borders. It is an outrage that Western nations preach free trade while blocking poorer countries from selling us their goods; it perpetuates Third World poverty in order to protect First World jobs. I’ll suck up a lot of lost Aussie culture and Planet Hollywood stores to get rid of that.

Idiot Does Stupid Thing

![]() Okay, look, yes: I realize

some idiot

has auctioned his forehead for advertising space, and January is a slow month for the media

so they’re all

writing articles

about it. And yes, of course, some idiotic company is going to pay some idiotic amount

of money for it, and that’ll make news all over again. (If you haven’t

heard about this, here’s all you need to know: his mother is proud of him because

he’s “thinking outside the box.”) Haven’t we already established that the world is

engaged in a slow, hapless slide into corpocracy? Do we really need to celebrate

every milestone?

Okay, look, yes: I realize

some idiot

has auctioned his forehead for advertising space, and January is a slow month for the media

so they’re all

writing articles

about it. And yes, of course, some idiotic company is going to pay some idiotic amount

of money for it, and that’ll make news all over again. (If you haven’t

heard about this, here’s all you need to know: his mother is proud of him because

he’s “thinking outside the box.”) Haven’t we already established that the world is

engaged in a slow, hapless slide into corpocracy? Do we really need to celebrate

every milestone?

Update (12-Jan-05): For a full listing of idiots, check out the hundred or so people currently offering various parts of their anatomy for sale as billboards (thanks to M. Burns for the link). Two items are worth a look, though: first, the “Forehead Ad Blocker” (screens out ads on idiots’ foreheads), and “Watch me bitch slap everyone selling their forehead”. Now that’s tempting.

24 comments

24 comments